Brent Johnson wasn't the first, best, winningest, or most recognizable mutual teammate of Alex Ovechkin and Sidney Crosby. The retired NHL goalie was never the primary starter for Ovechkin's Washington Capitals or Crosby's Pittsburgh Penguins, and he didn't backstop either player to a Stanley Cup. But he was around for the start of their rise. It shaped his thoughts on what makes them amazing.

During the 2005-06 season, the NHL's first after a yearlong lockout, Johnson backed up Olaf Kolzig for a rebuilding Capitals team that had little going for it but a sensational young Russian winger. Nowadays, expecting Washington and Pittsburgh to compete for titles is common sense; the same goes for Ovechkin and Crosby lighting up opposing goalies. They debuted in the league together as top picks from consecutive drafts, and Johnson had front-row access to their rookie breakouts. Ovechkin bagged 52 goals, and both players eclipsed 100 points, instantly validating enormous hype.

"From early ages, people around the hockey world have known about their greatness. They've known about their abilities. Maybe Alex went a little bit more under the radar, just because he wasn't in North America early. We all heard about Sidney Crosby as the next coming," said Johnson, who's now a Capitals studio analyst for NBC Sports Washington.

"They're able to perform at such a high level despite the pressure that's being put on them. Some players who aren't really (great), I think, would fold a bit under pressure. They never seem to. They never seem to fold. They never seem to falter."

The observation is as relevant as ever entering 2020-21, Crosby and Ovechkin's 16th season battling head-on for team and personal superiority. Their overlap has defined a hockey generation, and the rivalry is about to intensify. Starting Sunday in Pittsburgh, eight Penguins-Capitals games beckon in the realigned, hypercompetitive East Division - eight clashes between fading yet hopeful contenders long conditioned to dislike and irk each other.

Hockey's emphasis on team sometimes compels players to downplay individual battles. Penguins versus Capitals is what matters on the scoreboard, not Sid versus Ovi. But it's obvious why plenty of fans and talking heads, plus the occasional out-of-town writer, gravitate toward the latter framing.

| 2021 matchups | Date | Time (ET) |

|---|---|---|

| WSH @ PIT | Sun. Jan. 17 | Noon |

| WSH @ PIT | Tues. Jan. 19 | 7 p.m. |

| WSH @ PIT | Sun. Feb. 14 | 3 p.m. |

| WSH @ PIT | Tues. Feb. 16 | 7 p.m. |

| PIT @ WSH | Tues. Feb. 23 | 7 p.m. |

| PIT @ WSH | Thurs. Feb. 25 | 7 p.m. |

| PIT @ WSH | Thurs. April 29 | 7 p.m. |

| PIT @ WSH | Sat. May 1 | 7 p.m. |

Crosby and Ovechkin cross paths all the time, the result of their draft status, divisional proximity, and success in revitalizing once-stagnant franchises. The four postseason series they've played each produced a Cup champion: Pittsburgh in 2009, 2016, and 2017, and Washington in 2018. If Crosby and Ovechkin both dress as expected Sunday, it will be their 53rd regular-season meeting.

Wayne Gretzky and Mario Lemieux, titans of another era, never met on the ice even half as often.

Assuming good health - a surer bet for Ovechkin than for Crosby - new accolades await both stars in 2021. Each is very likely to record his 1,300th point. Crosby's nearing his 1,000th career game. If Ovechkin scores 36 goals, he'll climb from eighth to fourth on the all-time leaderboard, surpassing Mike Gartner, Phil Esposito, Marcel Dionne, and Brett Hull en route. If he scores 30, he'll have done so for a record 16th straight season, eclipsing a mark he shares with Gartner.

These distinctions are tributes to Sid and Ovi's longevity, as was this recent compliment from Capitals head coach Peter Laviolette: They've been hockey's best players for most of his 20 years in the league.

"There are younger players coming now who want to challenge that," Laviolette said during training camp. "But for so long, when those two teams, Pittsburgh and Washington, squared off, they made noise. They made noise because of those guys."

Conor Sheary, the former Crosby linemate who signed with Washington in December, offered similar sentiments.

"I think they're two generational talents who gave this league life. Normally, they put people in the stands," he said. "From my standpoint, I started with Sid in Pittsburgh (in 2015). Playing alongside him, he gave me a chance to break into this league, which is awesome. Moving to this side of the rivalry, I'm excited to be a part of it.

"Just to be a part of it with Ovi is pretty special - to be able to play with him, too."

Sheary is one of four ex-Penguins skating for Washington this season, joining Carl Hagelin, Daniel Sprong, and Justin Schultz. Historically speaking, the members of this group are in select company. They know firsthand - or soon will - what makes both Crosby and Ovechkin tick, acquiring a teammate's insight into their personality differences and the traits that bind them. As Johnson put it, "I got to see both sides of the story."

Crosby and Ovechkin's past mutual teammates

| Player | First teammate | Second teammate |

|---|---|---|

| Rico Fata | Crosby (2005-06) | Ovechkin (2005-07) |

| Kris Beech | Ovechkin (2005-07) | Crosby (2007-08) |

| Brent Johnson | Ovechkin (2005-09) | Crosby (2009-12) |

| Eric Fehr | Ovechkin (2005-11‚ 12-15) | Crosby (2015-17)* |

| Brooks Orpik | Crosby (2005-14) | Ovechkin (2014-19)** |

| Matt Cooke | Ovechkin (2007-08) | Crosby (2008-13) |

| Chris Bourque | Ovechkin (2007-09‚ 09-10) | Crosby (2009-10) |

| Matt Niskanen | Crosby (2010-14) | Ovechkin (2014-19)** |

*Won 2016 Stanley Cup with Penguins

**Won 2018 Stanley Cup with Capitals

The contrasts in how Crosby and Ovechkin approach the game have been evident since they were teenagers. The Penguins captain is the serious, calculated, pass-first genius who surveys the ice like a chessboard, thinking moves ahead like Gretzky. From the start of his NHL career, Johnson said, Ovechkin has been the physical, jocular, fun-loving powerhouse who seeks to impose his will in 45-second bursts.

And yet they're also fundamentally similar. During his nine seasons with the Capitals and a 107-game stint with Pittsburgh, Eric Fehr took note of both players' tireless efforts in practice: Crosby is the classic first-on, last-off type, while Ovechkin devotes time each day to perfecting his shot.

"They're both super intense when they're playing," Fehr said, and that shared killer instinct is symbiotic. Especially when they were young, Fehr and Johnson recall, each star truly cared about outdoing the other, forcing the opponent to play at his absolute peak.

"To whoever was out there saying Ovechkin is the better player or Crosby is the better player, they wanted to prove that they were," Johnson said.

New York Islanders head coach Barry Trotz, who coached Ovechkin to the Stanley Cup in 2018, affirmed as much.

"I had the pleasure of being a part of that rivalry. It's fierce," he said. "They don't like each other. They never have, and they never will."

Crosby, for his part, said last season that his relationship with Ovechkin has always been cordial, if distant: "We're not best buddies, but at the same time, I respect the way he plays and what he's doing; can relate to the pressure and the expectations he (faced) coming into the league."

To that last point, Trotz praised both for shouldering an immense burden after the 2005 lockout. Before either player came close to winning a Cup, their brilliance kept the league interesting and relevant at a time when fan support could have cratered.

Their brushes have always been electric and consequential. Fehr played in the 2009 playoff game that both stars punctuated with hat tricks. He scored twice in the 2011 Winter Classic at Heinz Field, the site of Crosby's first costly concussion, and he loved facing the Penguins in feisty matchups in D.C. on Super Bowl Sunday (it's happened four times in the Crosby-Ovechkin era). Winding down his career in Switzerland, the 35-year-old center said he's thought about Crosby and Ovechkin's bond from a big-picture perspective.

"I never saw the games with Wayne and Mario. But I would have to assume that this would go down as the best rivalry in hockey history. Because they were in the same division. Because they were both able to win Cups out of it. Because they've met up with each other so many times, and they had great games against each other," Fehr said.

"You'd have to put a bunch of options in front of me. But I'd have a hard time believing there's (been) a bigger rivalry in the NHL."

About those options.

Picking the NHL's all-time best player rivalry depends on how you define the term, or at least on the element you prioritize: mutual hatred, frequent high-stakes matchups, the simultaneity of two pursuits of greatness. Taking into account the skills and accomplishments of Crosby and Ovechkin, each era has its equivalent pair of superstars.

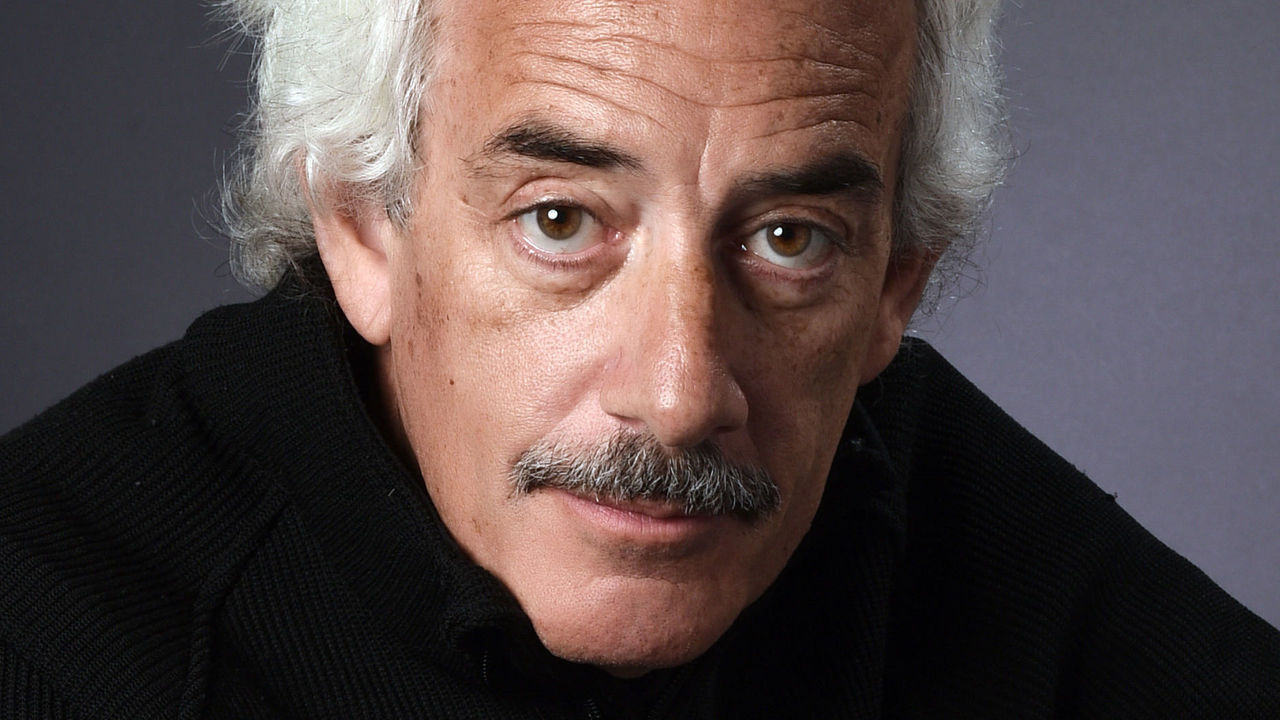

Gretzky and Lemieux were those legends in the 1980s and '90s. The Montreal Canadiens and Boston Bruins owned much of the 1970s, led by top talents Guy Lafleur and Bobby Orr. Of the players who dominated the prior few decades, said hockey historian Eric Zweig, two stand out from the fray: Maurice Richard and Gordie Howe.

Individually, Gretzky headlines the GOAT conversation, and Lemieux probably has an inside track on the top five. Yet despite overlapping in the NHL for 13 seasons from 1984-97, the two faced off a mere 25 times. Lemieux's Penguins were bottom-dwellers when Gretzky's Edmonton Oilers were in their prime. They were never divisional or conference foes; they didn't contest a single playoff series. Predictably, their head-to-head stats pop, but as Zweig told theScore, the league never stoked or marketed their rivalry with the same zeal as Sid and Ovi's.

| Matchup | GP | G | A | PTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gretzky vs. Lemieux | 25 | 15 | 45 | 60 |

| Lemieux vs. Gretzky | 25 | 11 | 27 | 38 |

| Matchup | GP | G | A | PTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crosby vs. Ovechkin | 52 | 26 | 48 | 74 |

| Ovechkin vs. Crosby | 52 | 30 | 21 | 51 |

In the '70s, knee surgeries cut short Orr's prime and snuffed out a potential rivalry with Lafleur. The Bruins and Canadiens met in four playoff series that decade: one right before Lafleur was drafted, and three - including the 1977 and 1978 Stanley Cup finals - just after Orr left Boston.

A closer comparable to Crosby-Ovechkin might be Lafleur-Dionne, which featured the top two picks of the 1971 draft. Dionne ranks sixth in NHL history with 1,771 points. Lafleur sits 27th. But where Lafleur paced the Habs to five Stanley Cups, Dionne's Detroit Red Wings and Los Angeles Kings teams were generally bad or mediocre, depriving him of widespread, breathless media coverage and the opportunity to compete for those championships.

"We all knew who he was and that he was a great player, but you never saw him. You never heard stories about him," Zweig said. "I don't think you ever hear about (Lafleur-Dionne) as a classic rivalry. It sort of should be. Should have been, I guess."

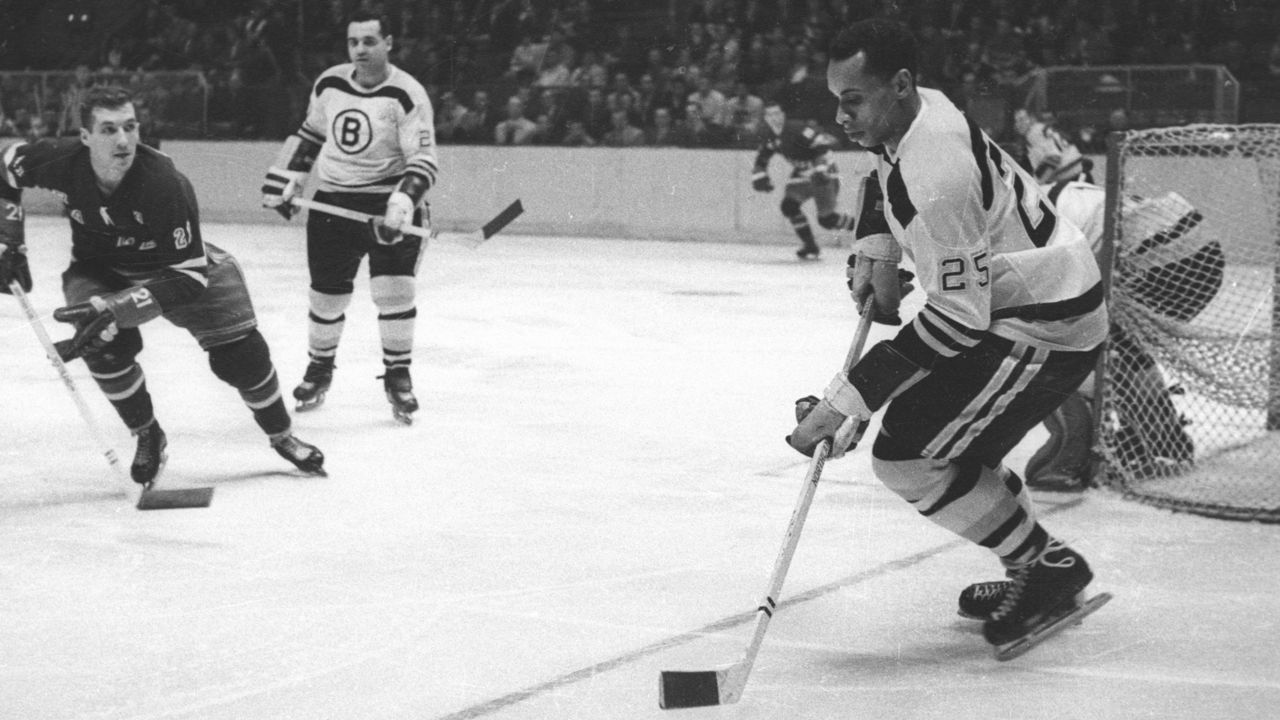

Instead, to Zweig, Howe-Richard "is the classic (rivalry), at every level." From Howe's 1946-47 rookie season to Richard's retirement in 1960, their teams were the toast of the Original Six. Either the Red Wings or Canadiens appeared in every final during that span, and they combined to win 10 Stanley Cups, with Howe and Richard meeting in the finals three times. Not that they only brought the heat in the playoffs. Dan Holmes of Vintage Detroit Collection once recalled the events of the first NHL encounter between Richard and Howe: The Rocket elbowed Howe in the chin, and the future Mr. Hockey responded that same shift with a right haymaker.

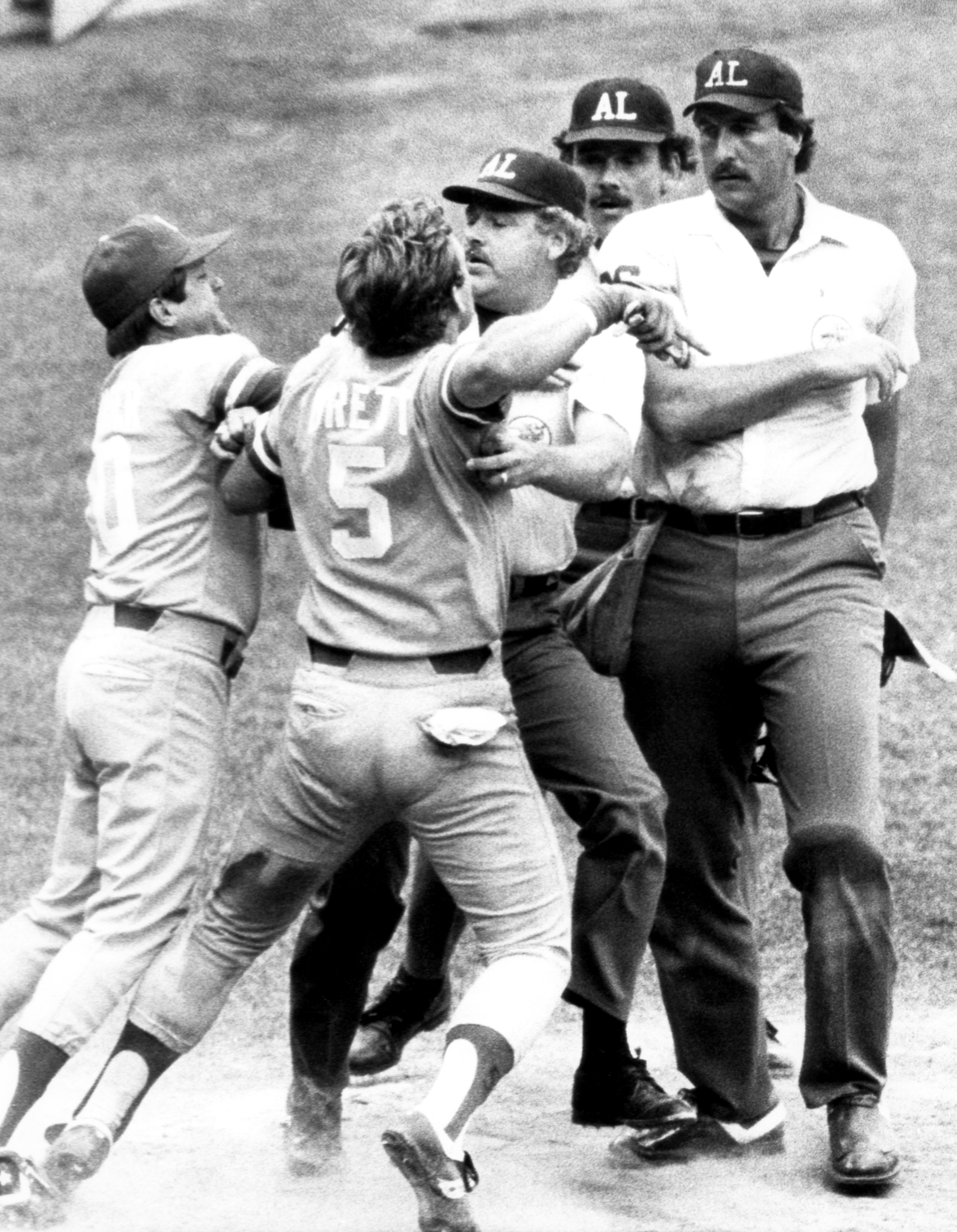

Ovi and Sid about to go at it 👊🏻 pic.twitter.com/9ZsQqDgOlA

— NHL Chirps (@nhlchirpz) December 20, 2018

Even in a less violent, less acrimonious era, Crosby and Ovechkin have engaged in their share of scrums and shouting matches, including the 2018 tiff depicted above. But their rivalry, Zweig said, lacks the subtext of Howe and Richard's: the younger player aiming to usurp the incumbent superstar. Jean Beliveau, Bobby Hull, and Stan Mikita all excelled in the Original Six age, but Howe and Richard were in the NHL first, a budding all-around great from Saskatchewan farm country challenging the rule of the French-Canadian icon who was the game's purest scorer.

"You're trying to take it away from me," Zweig said, summarizing the stakes for the older Richard. "I've been the guy, and now here comes you."

This century's equivalent storyline has seen Crosby pull away from Ovechkin in Cup wins, with the Penguins clinching three before the Capitals earned their first. The 13-year, $124-million contract Ovechkin inked in 2008 expires after this season, and he hopes eventually to finish his career in Moscow. But he's also said he intends to stay in D.C. past 2021, and though their East Division competition is strong, time remains for both Washington and Pittsburgh to try to avenge recent playoff disappointments.

Invoking his own historical comparison before the season started, Trotz said Crosby and Ovechkin will one day be remembered as "the Howe and the Hull" of their time: one a paragon of offensive consistency (Crosby's 1.28 points per game ranks sixth all time among 500-point scorers), and the other capable of surpassing Gretzky in goals. Thanks to Washington's 2018 breakthrough, both will also go down as winners - their unifying motivation.

"A lot of people were right on the mark," Johnson said, reflecting on the buzz Crosby and Ovechkin once commanded as No. 1 picks. "They had these two guys come in the league, and (they) said how absolutely unbelievable these two guys were going to be."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.

Copyright © 2021 Score Media Ventures Inc. All rights reserved. Certain content reproduced under license.