He made a name by throwing punches and hits, but that wasn't what made Dennis Bonvie a legend.

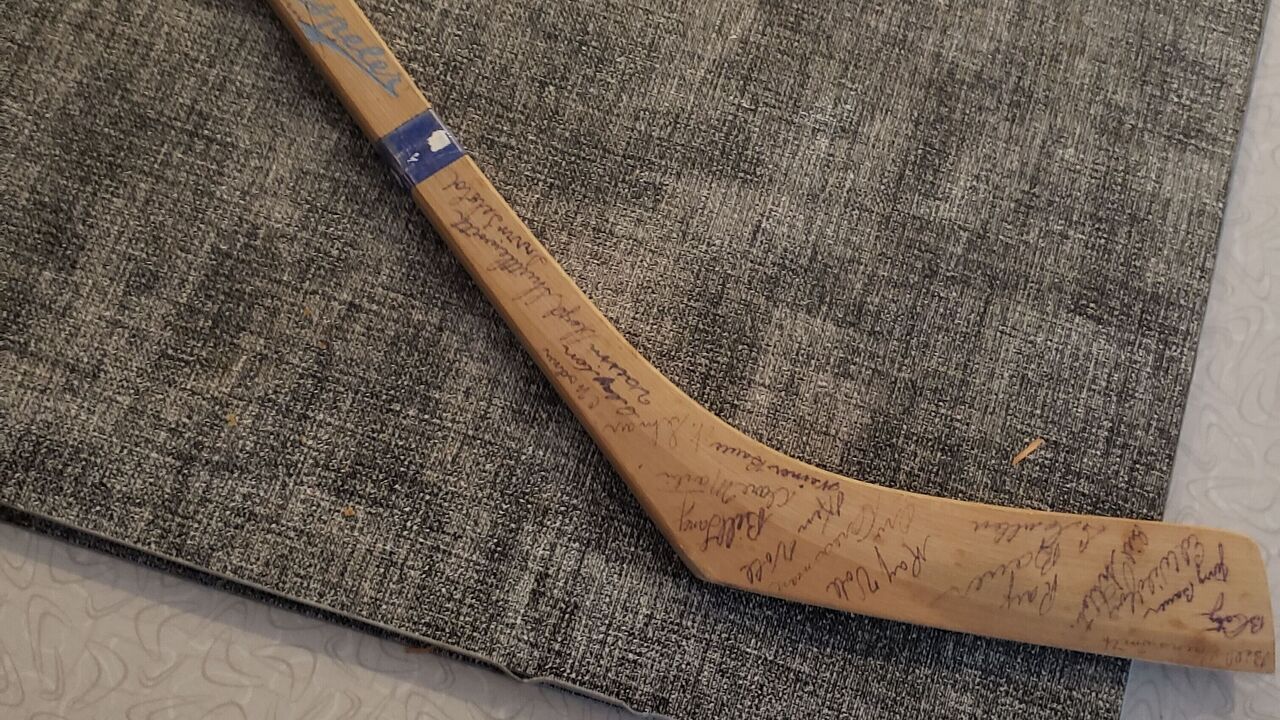

When he retired in 2008 after a 15-season pro hockey career, he'd amassed an unassailable record of 4,493 penalty minutes in the American Hockey League, more than 1,500 ahead of his closest challenger and enough to earn him an induction into the league's Hall of Fame on Feb. 5 at the All-Star gathering in San Jose.

He fought in all levels of the game. From Junior A near his hometown in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, up to the NHL for the Oilers, Blackhawks, Penguins, Avalanche, Bruins, and Senators - wherever he could find a team needing two fists with something to prove. He fought top enforcers in an age when that role was inseparable from the game itself. If you ask, he'll reluctantly rattle off the biggest matchups. Bob Probert. Tie Domi. Gerry Fleming. One bout against Ryan VandenBussche lasted more than two minutes.

He fought until his hands were crooked and his body was spent.

But say the name Dennis Bonvie to anyone who played with him or crossed paths with him during his subsequent 15-year career as a pro scout - that is to say, much of the hockey world - and you won't hear a lot about fights, at least not at first. You're likely to hear a quiet laugh, a sigh, and the words: "Bonvie was a good teammate."

It wasn't just that Bonvie took penalties - it was the way he did it, with almost every minute of his HOF record traceable to a teammate he was protecting, some in less traditional ways than others.

"I wasn't one to drop the gloves at all, but I remember I had gotten into my first fight," says Stephen Dixon, a fellow Maritimer who played with a veteran Bonvie as an AHL rookie for the Wilkes-Barre/Scranton Penguins. "I went to the penalty box and I looked over and Dennis is standing up, giving me the thumbs up and talking to the coach. All of a sudden, they're getting the puck ready for the faceoff and Dennis jumps on, lines up next to a guy, and his gloves come off. He's in a fight as well."

Bonvie arrived in the penalty box with a grin. "Stand up and give me a hug," he told Dixon. "It's your first fight. I'm not going to let you sit in the penalty box alone.

"He sat there with his arm around me the whole five minutes."

For Bonvie, that three-word distinction - a good teammate - was the highest honor in hockey. "Hopefully that stands for what I did, for as long as I did it," he says.

That Bonvie had the career he did - he retired months shy of his 35th birthday - is owed, from start to finish, to his burning desire to stick around long enough to play another game. "There's nothing like being on a team, and there's nothing like competing," he says.

His career began rather inauspiciously in 1991 when he was drafted into the Ontario Hockey League by the Kitchener Rangers. He went in the 19th round, 277th overall, the sixth-last pick of the draft. "I think the janitor called my name out," he likes to joke.

He was later traded in a package to the North Bay Centennials and that's when he knew fighting would be his path up. "The coach said he liked tough Maritimers and I fit the bill. I told him I wanted to be the toughest guy in the league. I said, 'Just give me a chance to prove my worth.'"

Bonvie got to work, tallying 261 penalty minutes in 49 games in his first season and 316 penalty minutes in 64 games the next. But the effort wasn't enough to get drafted into the NHL. After a tryout with the Flames went nowhere, he enrolled in university back in Nova Scotia, but never made it to class. Instead, he reported to a tryout with the Cape Breton Oilers, then Edmonton's farm team, and his illustrious AHL career began.

"At first when I went there I was worried there wasn't a spot for me, maybe they didn't want to keep me around," he says. He promptly made himself useful by switching from defense to forward to fill a gap in the lineup. "I knew I was the underdog, I knew I was trying to prove I belonged."

While he was still trying to impress front offices, Bonvie already had the confidence of his teammates.

"My first experience with Dennis was when I got sent down to Cape Breton and got thrown into the lineup," says former Oiler Louie DeBrusk, who knew how to defend himself on the ice. "The first scrum that I get into in front of the net, I'm thinking the gloves are going to come off. All of a sudden he comes into the pile and separates me from another guy and wants to fight him. And I'm thinking, 'That might be the first time in my career that somebody actually stepped up for me.' He was so game. That was how the AHL was back then. There was a lot of toughness and a lot of skill. Dennis felt like he was protecting his players, which he did. And he was one of the best ever at it."

It was his work ethic, too, that gained notice. "I remember watching him lift weights after practice, he'd be in there bench pressing, he was just all-in," DeBrusk says. "He had that burning desire to make it. He never got satisfied. He was never content. He always felt like somebody could take his job on a nightly basis. You had to have that attitude in that role. Every single day, somebody might be looking to try and take your job. He was going to do whatever he could to make sure that didn't happen."

Bonvie didn't have to wait long for his big shot. "When I started, I wanted to prove and get respect from all my peers that I could do it, that I was as tough as everybody else. In doing that, you start thinking: maybe there's a chance I could play a game or two in the NHL."

By the 1994-95 season, what started as an outside chance at the NHL became a reality when Bonvie made his debut in Edmonton in a late-season game against the Kings. In his first shift, Bonvie immediately tried scrapping with L.A. enforcer Matt Johnson. When that didn't happen, Bonvie remembers the Kings dumping the puck into the Oilers' zone and bringing on their first line - anchored by Wayne Gretzky. "I think I just dumped it in and went off the ice, I was kind of in awe," says Bonvie. "Welcome to the show."

Bonvie spent the rest of his career going up and down from the AHL to the NHL. "I played 15 years just trying to play one more game." He collected 92 total NHL appearances.

"Every time you get called up to the NHL is the best day in the world; every time you get sent down, it's the worst thing in the world," DeBrusk says. "It's a really emotional roller coaster going up and down and trying to make the NHL on a regular basis."

But if the emotional whiplash ever wore on Bonvie, he didn't let it show. "I just love to play. I love to be part of a team. I loved to protect my teammates and make sure they felt comfortable. At first you start and you're trying to get up in the NHL. You're trying to get another opportunity to get up when you get sent down.

"Then, you get halfway through your career and realize, 'You know what, I might end up spending a lot more time in the minors.' Well, then you have to try to be the best veteran you can be and try to develop those kids."

Growing up in Nova Scotia provided Bonvie with the perfect framework for how to build community. "In Nova Scotia, you just drop in," his wife Kelly Bonvie says. "You just drop in to people's houses, you end up staying for dinner, there's always enough, and the door is always open."

"My mom was a tremendous cook," Dennis says. "My dad would come home on weeknights from the mill and my mom would always have meat and potatoes. Sunday was family dinner. Whatever holiday it is, you go to somebody's house and everybody is there. We were brought up like that."

So Bonvie brought that family tradition to his team. "I'm not sure if you can print about the bottles of wine at these dinners because that's what I remember," says Chris Kelleher, who played with Bonvie in Wilkes-Barre and who is now the Minnesota Wild's director of player personnel. "He'd invite anyone - rookies, veterans, whoever it was."

"He wouldn't want anybody to feel left out," Kelly Bonvie says. "He just wanted to make sure that these guys felt supported and there was always somebody to go to if they had a problem. I look back and I really treasure the memories of hanging out with some of these guys. You know, they were still growing up and they just appreciated having a home-cooked meal. It was just the simple things that they really appreciated. We were happy to be able to do it."

The dinners often led to swapping tales about on-ice antics. "When Dennis was around, he was always telling stories," says John Slaney, now an assistant coach for the AHL's Tucson Roadrunners. One of the favorites that still gets retold is a famous one-liner Bonvie would feed the opposition.

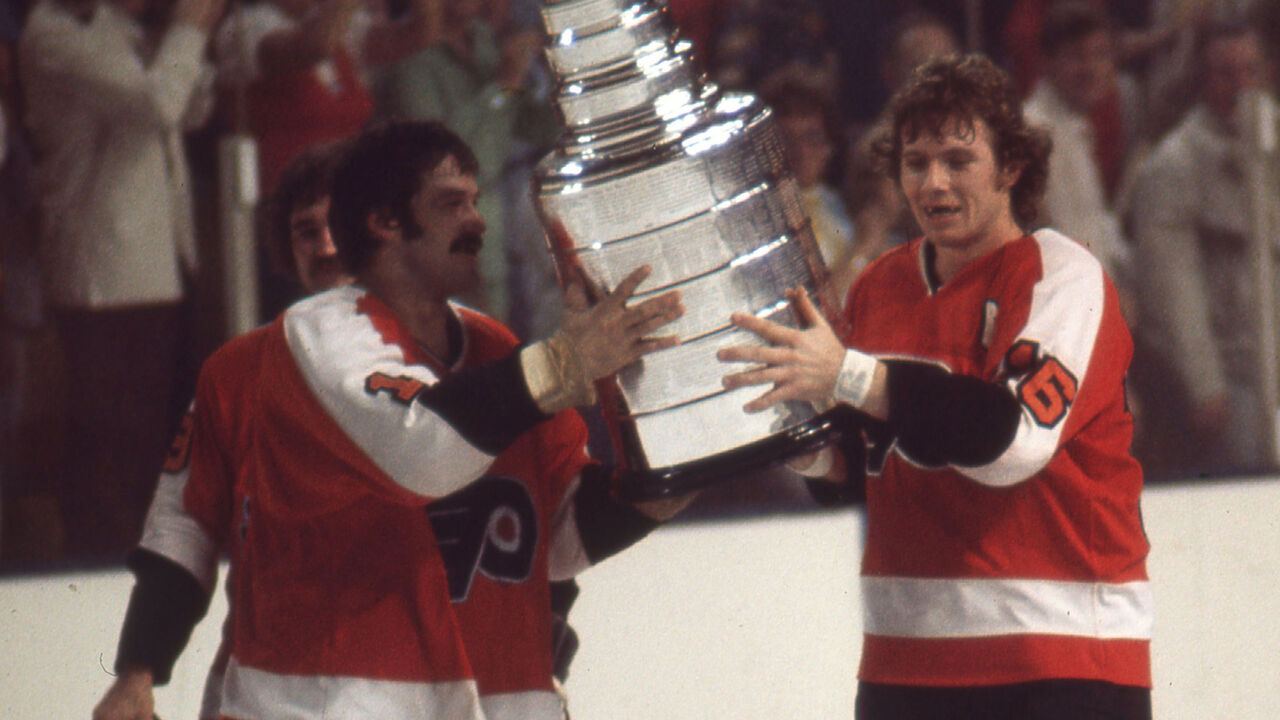

Kelleher's version of it takes place in Philadelphia. "Dennis was really our only legitimate, tough-guy fighter. He could fight anybody, right? So we go to Philly and everybody's nervous. Dennis was trying to keep it light. The puck doesn't even drop and he goes over to the Philly bench. He says to them, 'I got three fights in me. You guys decide which three it's going to be. Now let's drop the puck," Kelleher says. Three fights were the league maximum before getting ejected.

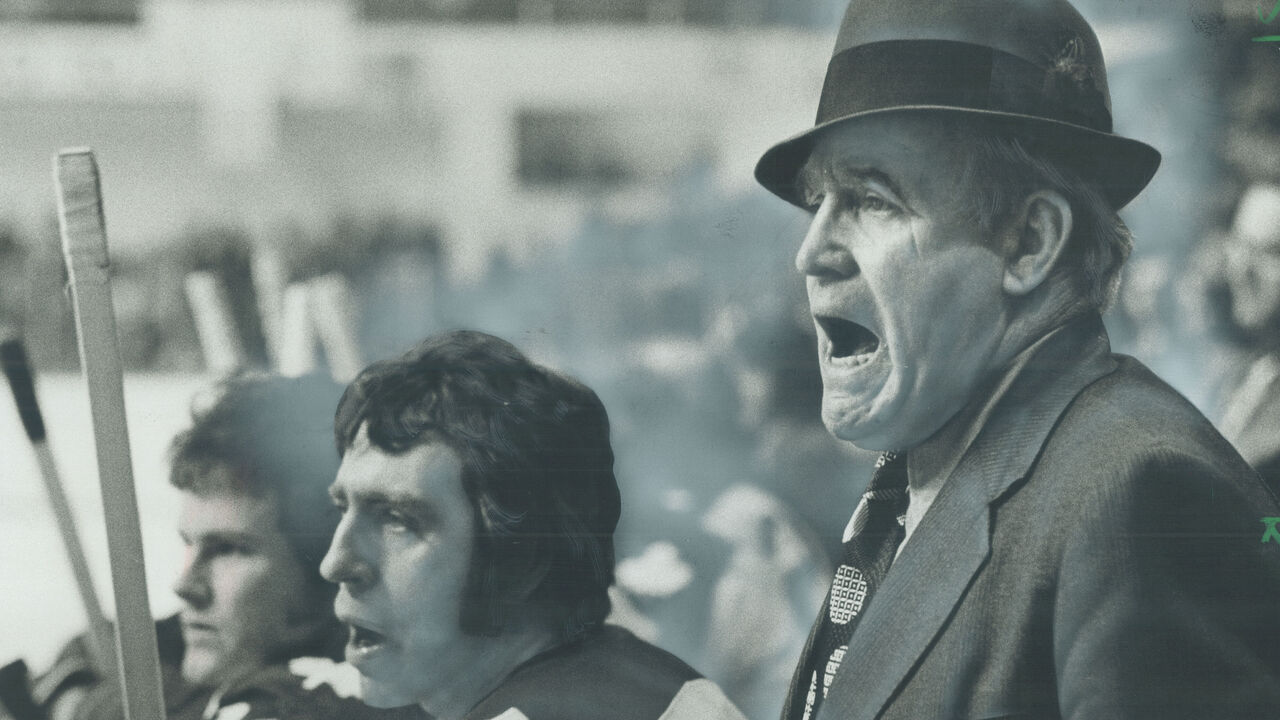

"He had a lot of chirps," Slaney says. "He would yell at the bench if everyone was looking down, 'Hey, did you lose all your quarters on the floor?' When Dennis got mad it was almost like when your grandfather got mad."

Bonvie became the first person to call when you needed someone. "I played one game in the NHL," Kelleher says. "It was for the Bruins. I got called up. The morning of the game, I realized with the travel schedule, I was going to get to the rink at 9 a.m. - I was just going to sit there for hours getting more nervous. So I called Dennis up. He played for the Bruins at the time. And he met me at the rink and sat with me. He was more excited for me than I was. That's something I'll never forget."

That empathy and leadership carried well beyond Bonvie's on-ice career and into his scouting pursuits. He's now the Bruins' director of pro scouting.

"What I admire most about my dad is how much time he makes for us," his 19-year-old son, Rhys Bonvie, says. "Sometimes he'll take me along to NHL games and I love being in the press box with him. He knows everyone. Even the elevator lady. He says she's the one who knows everyone but I know it's him, too."

Rhys says people who know he's Dennis' son assume he must be tough, like his father. But tough isn't the word he uses to describe his dad. "I would say he's a teddy bear," Rhys says.

Bonvie's never hidden that soft side off the ice. Learning about his HOF induction openly brought him to tears. "He called me and he couldn't even talk," Kelly says. "He was just so emotional. I was just so grateful that his hard work for all those years got recognized."

With hockey having changed drastically in the nearly two decades since Bonvie's heyday, with far more emphasis on skill and speed, his on-ice accomplishments might be overlooked. But many former players have pointed out that Bonvie's stats speak loudly: he had 84 goals and 191 assists in the AHL, so he could do more than fight. But still, his main role has become a bit of a throwback to a different era of hockey.

"It's an entirely different game," DeBrusk says. "Players like Dennis, the role that he had, call it the enforcer, call it the tough guy, you can even call it the goon, I really don't care. I think when you look over the history, they were so influential on how the game was played. They were incredibly popular in every market they played in - whether it was negative or positive, people knew who those guys were.

"I think Dennis worked hard, harder than anybody. I don't think people really understand how difficult that position is, to do it on a nightly basis and for as long as he did. The toughness is what got him to pro hockey, got him a job. But to stick around for as long as he did, you have to be a good teammate."

For Bonvie, when he reminisces about his Hall of Fame career, that's what he's usually thinking about. "I don't even like to talk about the fights too much because it's not fair to the guys I was fighting or vice versa," he says. "There's ones that I lost that I shouldn't have, and the ones that I did really well in I don't need to talk about because it could have been me on the other side. Proud of them? I just did my job."

Instead, Bonvie's far more proud of the designation he earned from the chirps, the dinners, from showing up when he was asked: "A good teammate."

"(A) coach told me way back in the day that when you retire, if your teammates can stand up and say, 'That was one heck of a teammate, a really good guy,' that's something to be proud of. I think I was the best teammate I could be."

Jolene Latimer is a feature writer at theScore.

Copyright © 2024 Score Media Ventures Inc. All rights reserved. Certain content reproduced under license.