They're the TikTok generation, and they're changing sports as we know it. As Gen Z gains increasing purchasing power, all areas of sport are feeling their influence.

Gen Z doesn't think or act like fans of yesteryear, so their alternative approach to sports consumption means leagues and teams must rethink their marketing strategies. Capturing their attention is vital to maintain the revenue growth sports have enjoyed for decades.

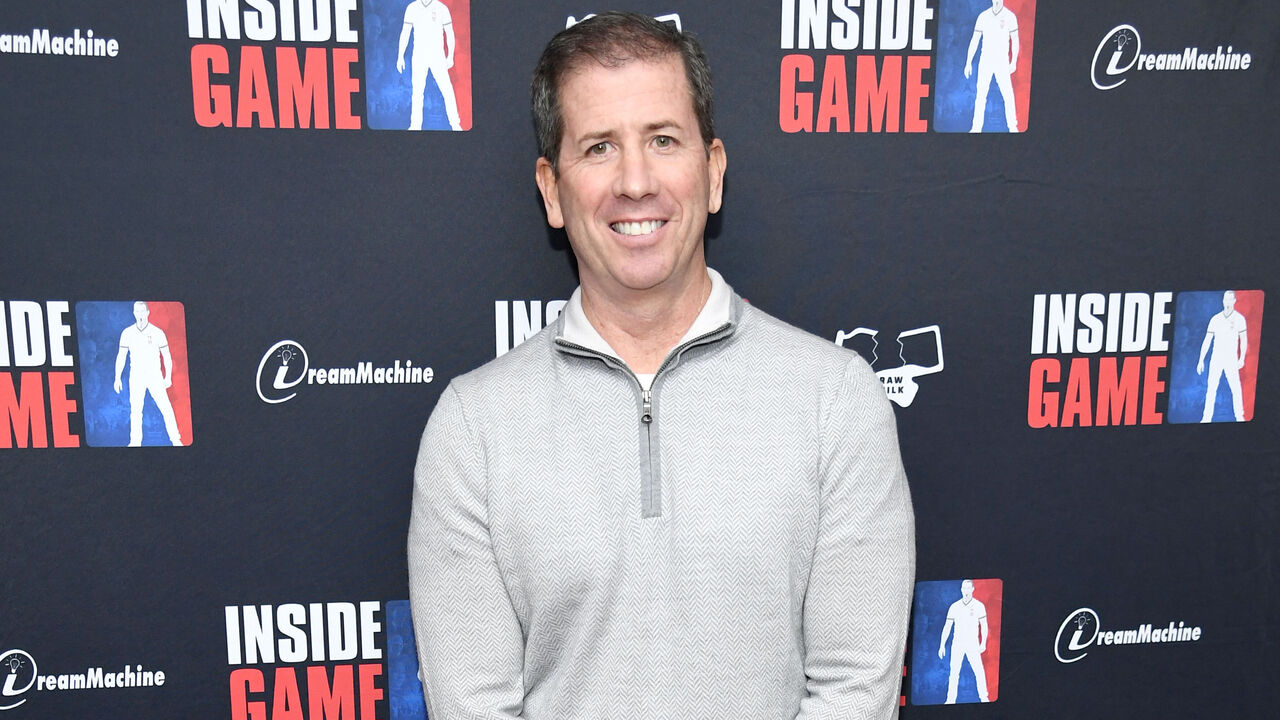

"The traditional mindset fan is someone who watches the broadcast or buys tickets and goes to the game," said Heidi Browning, the NHL's chief marketing officer. "But that's not how this generation thinks. They can consider themselves fans of sports by following content and following athlete stories without ever even attending a game."

Research by Morning Consult shows 33% of U.S. Gen Zers - defined as those between ages 13 and 25 - don't watch live sports broadcasts. They also don't watch them in person; almost 50% of Gen Zers in the 1,000-person survey said they'd never attended a live professional sporting event.

But none of that means they're not sports fans. "They still can engage in watercooler conversations with their friends, they still buy merchandise, they still aspire to be like certain athletes," Browning said. "So I think that we need to look broader into how we define fandom when we look at this next generation."

Part of Browning's strategy has been to engage hockey fans ages 13-17 on an annual youth advisory board that the league has been running for six years. Past participants range from all over North America - Hawaii to Newfoundland.

"The whole idea behind this program is to expose them to the business of hockey, while at the same time hearing from them how our marketing is resonating," Browning said.

theScore discussed the league's marketing efforts with Browning and the specific challenges of engaging the next generation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

theScore: What's the most surprising thing you've learned from working with the youth advisory board?

Browning: Something that's surprising is how much content they consume on a daily basis. Not only do they consume it, but they consume it on multiple channels. They have an opinion on it, they remember it, and they can give you perspective on it. The advice that they give to us is very practical but also inspirational for us and aspirational for us as we continue to shape our programs for the future.

Statistics show Gen Zers are both attending live sporting events less frequently and watching fewer broadcasts. Do you get the sense that Gen Z is watching sports less?

Browning: I think that they do watch sports, but they also look at sports through a different lens. It's not just about the game that's on the ice. It's the whole picture. By that I mean, they want to know the athletes, they want to know the human behind the visor. They want to know everything about them, their lives, personalities, families, and their interests. What are the causes they care about?

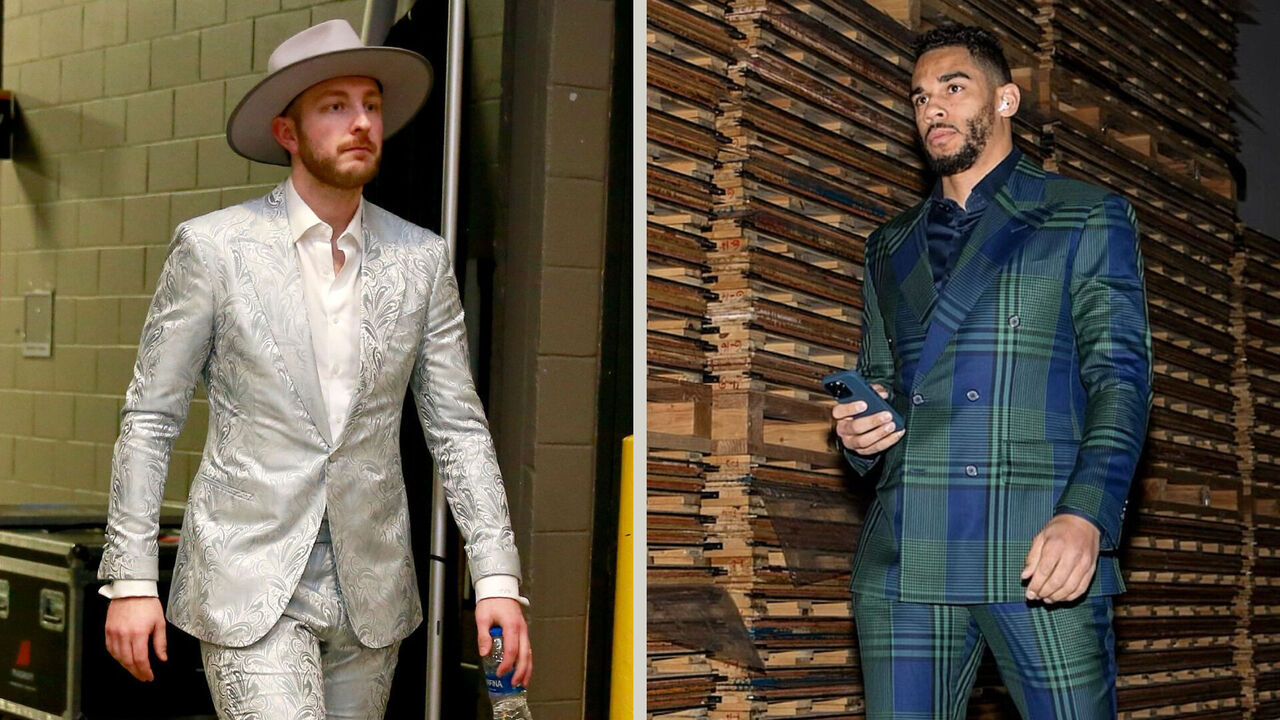

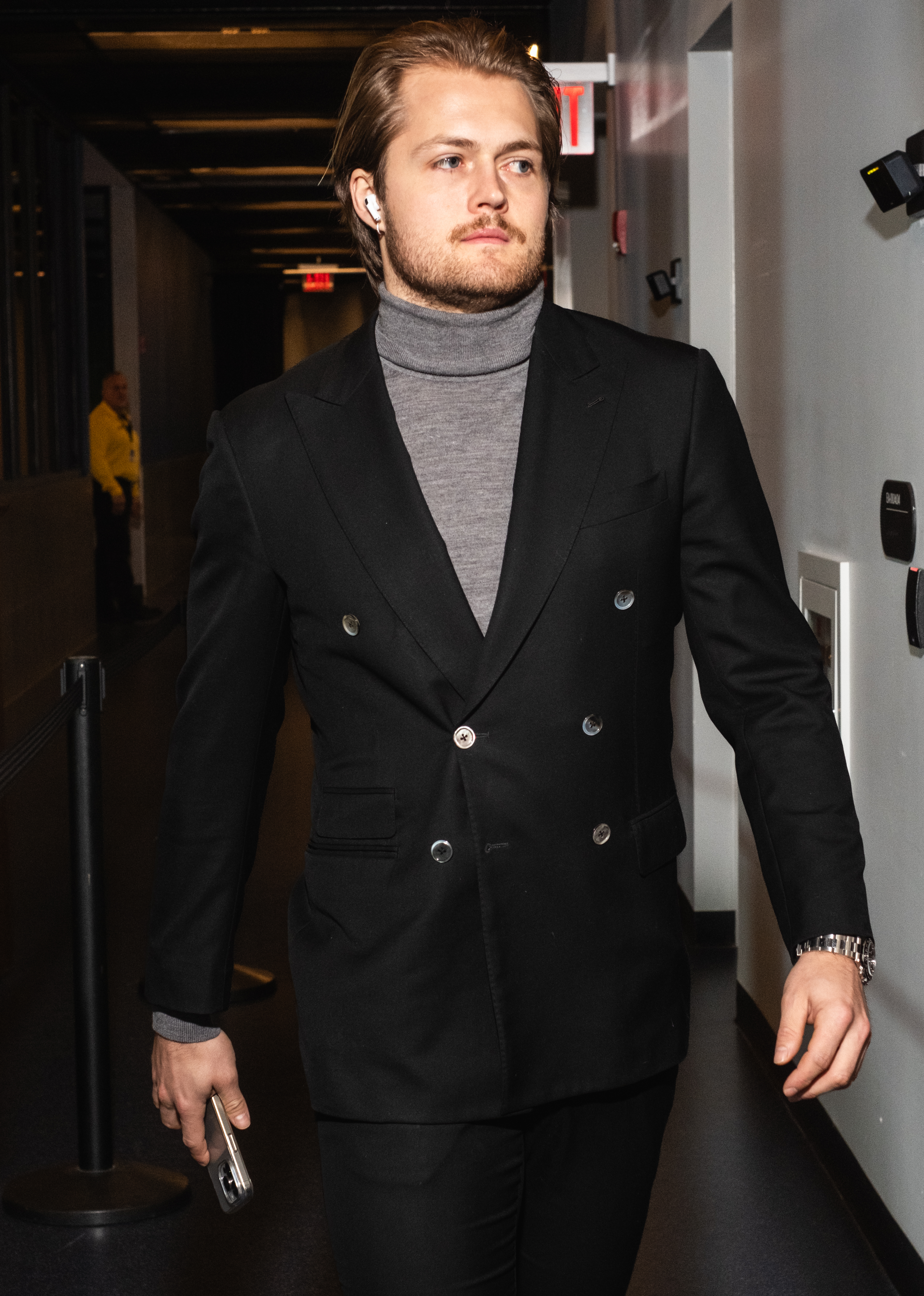

This idea of athlete-driven media is not just a hockey thing. This is a global phenomenon. So they'll follow athletes in the sport they love. They'll even follow athletes of sports they don't even watch just because they're interesting humans. It's pervasive across all sports, and it's a global shift.

@nhl Shesterkin & mini Shesterkin ❤️ #NHL #hockey #StanleyCup ♬ Criança Feliz - L. Comp. Project

Hockey culture has historically been more reserved, how do you meet the content needs of today's generation knowing NHL athletes tend to feel less comfortable sharing about their personal lives?

Browning: I think we've seen tremendous progress in hockey culture in players from the next generation who are willing to share and participate in social media. Whether you look at TikTok or Instagram, you see a lot more activity from players. Obviously, we'd like to see more of it. But we also want to make sure that whatever the players are doing, however they're participating on social media, that they feel comfortable and they're doing what's right for them and authentic to them, as opposed to trying to force them to do stuff that might not feel right.

Part of it is - how do we market our players? How do you market an individual player when we're clearly a team sport? Then the other part is, how much do the players want to participate in building their own personal brand, being out there on social media, doing interviews, and creating additional content? It's the choice of the player how much they want to lean into that.

@nhl all smiles at family skate ❤️ #NHL #hockey #StadiumSeries ♬ original sound - NHL

Are there any overarching themes that unite what you're learning from the advisory board from year to year?

Browning: We've really honed in on some key categories over the years that continue to morph and change. The first is called "humans are greater than highlights." That's really about the athlete and knowing their personalities. The other part of having that authentic kind of experience is the work we do with our creators - finding these hockey influencers that aren't professional players but have strong followings on their own.

My favorite story is about Zac Bell. We were first introduced to him in our Fan Skills At Home challenge during the pandemic, and he submitted a video of his incredible skills. Then, as we came out of the pandemic, his fandom continued to grow. As his fandom has grown, the fans that follow him have grown. What's so interesting is that they feel like they've been with him in his journey, so they're committed to him.

@nhl Double Dribble 🏀 #NHLFanSkills at Home presented by @geico (🎥 @alwayshockey ♬ original sound - NHL

The second is what we call "see me," and it's this idea of being noticed by a league, by a player, by a team, through a like or retweet or reshare.

So, it might be Fan Skills At Home, it might be ODR (outdoor rink) Week, it might be your playoff reactions. Any time that fans get that opportunity to share their fandom and their authentic selves and have it be acknowledged by a league, a team, or an athlete, that means everything to them.

The third is called "game on" and is about the gamification of everything. There's this idea that kids really like to show off their knowledge for the sport, they like to play little games to test their knowledge and see where they rank in a leaderboard with their peers. Any time we have the opportunity to use some of the native tools within social media, we try to introduce some form of gamification, like a highlight battle. Or, for the Stanley Cup Playoffs, we want to be able to engage people through a bracket challenge because that bracket challenge drives conversation, engagement, and awareness of the Stanley Cup Final.

What do you think will continue to help youth engage with hockey?

Browning: One of the core tenets of engaging the younger generation is inclusivity and accessibility. That's an area that we do spend a lot of time with our power players on. Many, if not all of them, have joined because they want to make the sport they love available and accessible to their peers and their friends.

We talk a lot about programs like NHL Street that are designed to get beyond some of those traditional barriers. You don't have to skate or have access to sheets of ice, we can put sticks in hands, and you can play street hockey within your community. That's been an increasingly important program throughout all of North America.

We're hockey humble and we don't often talk about the dollars that go to the communities, but our power players want us to talk about that more, emphasize all the great work that the clubs do and the league does as a whole to grow our sport. There are a lot of different ways to weave hockey into a young person's life, whether it's through education, physical activity, entertainment, or through community. These are the kinds of ideas that pop up and we talk about throughout the season.

Jolene Latimer is a features writer at theScore.

Copyright © 2024 Score Media Ventures Inc. All rights reserved. Certain content reproduced under license.