No one had done it before, and no one has done it since - but for three brief years in the 1980s, one man ascended the hockey hierarchy to climb from linesman to NHL team owner.

His name was Harry Ornest, and almost 40 years after he took control of the St. Louis Blues, his story has become a footnote in hockey history.

Fans who do remember him for saving the club from a dispersal draft often think of him as a bull in a china shop who ran the Blues, and later the CFL’s Toronto Argonauts, with a quirky brand of charisma and austerity.

But Ornest's story isn't one of chaos and conflict, although it does include some of that. It's the story of a man who worked 60 years to achieve his childhood dream, one he birthed as a Depression-era son of immigrants growing up on the Canadian prairies. Even having reached an age when many people are tempted to wrap up their life's work and enjoy what they’ve built, Ornest took the biggest gamble of all, putting his modest but self-made fortune on the line to achieve his lifelong vision of success. It's an ambition he saw to completion, even after the stress it caused led to an early heart attack.

For three improbable years, Ornest lived out his childhood dream.

The birth of a dream

Young Harry Ornest was obsessed with sports growing up in Depression-era Edmonton as the son of eastern European Jewish immigrants who ran a local general store.

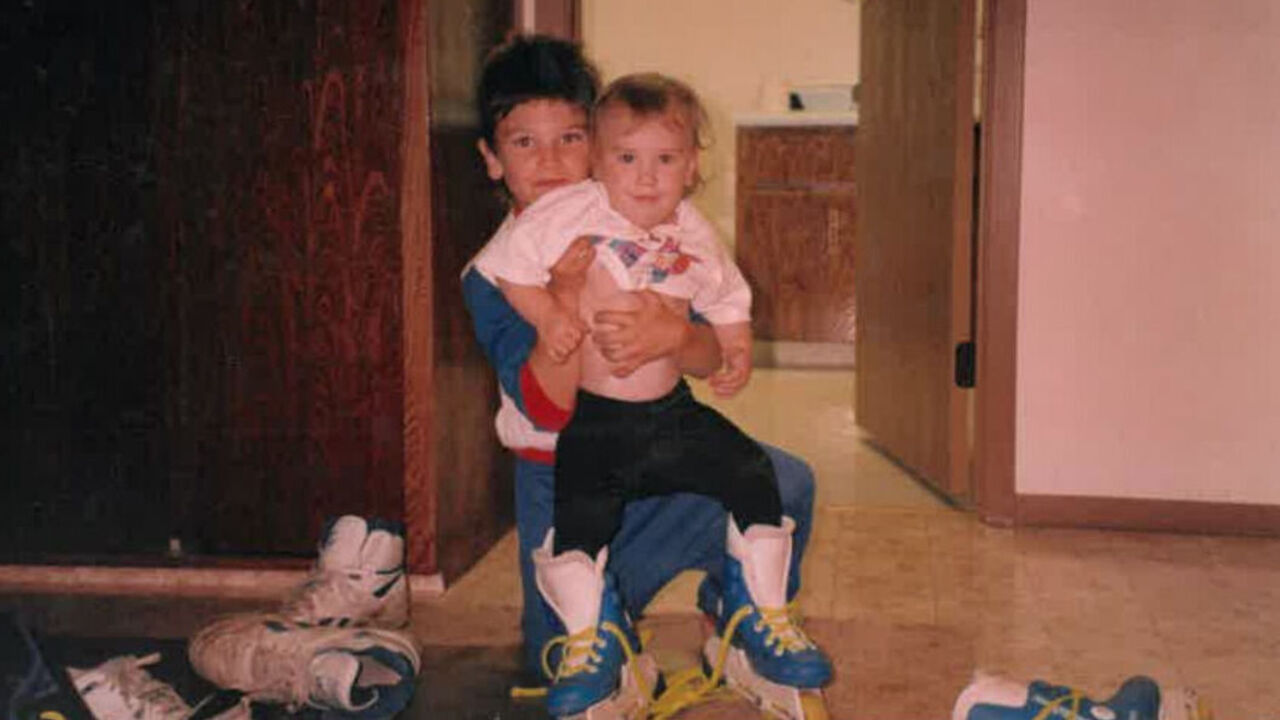

"Sports was his milieu as a kid," says Laura Ornest, who describes her dad as a "rink rat" who could always be found watching or playing hockey as a child. His naive childhood fantasies bounced between wanting to write about sports, play sports, or own a team. But for Harry, those daydreams rapidly turned into plans.

"It comes from wanting to be somebody," he later wrote in his private notes. "Everybody wants to be somebody. Some never get a chance. Some fall short for whatever reason. Some are prescient enough to pick the right parents. I picked the right parents, but we didn't have a dime. My story is not much different from millions of Depression kids of all racial backgrounds."

Eventually, his entrepreneurial inclinations took over, and team ownership was increasingly his goal, far-fetched as it might have been. To flex his business sense and support the family through the Depression, Ornest sold programs at the outdoor rink. Back then, Edmontonian Clarence Campbell was making headlines as a prominent NHL referee and figured among the local sports stars of the day.

"Being so poor growing up, they didn't have much money. Every dollar mattered. He was learning business from a very young age," Laura Ornest says.

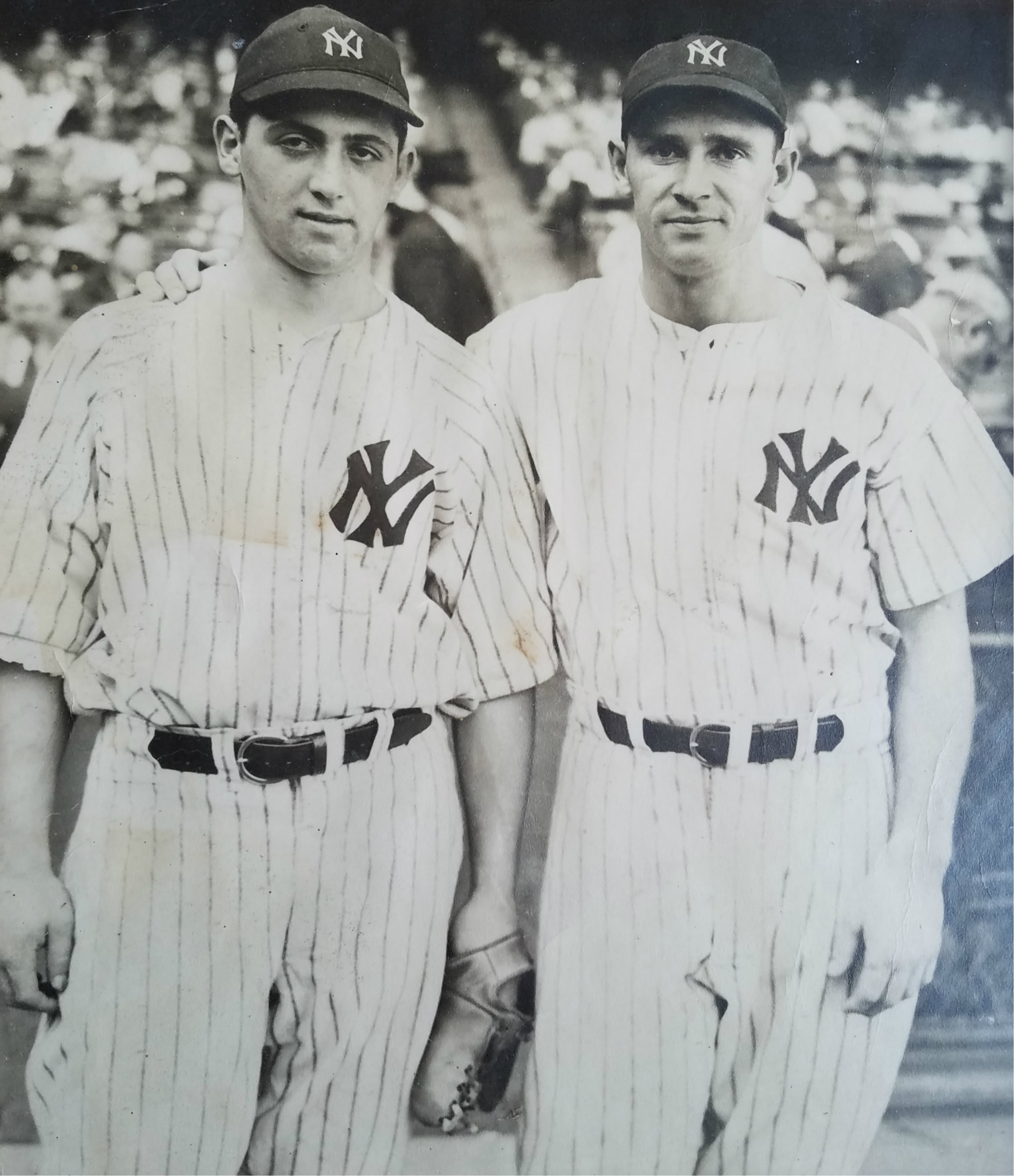

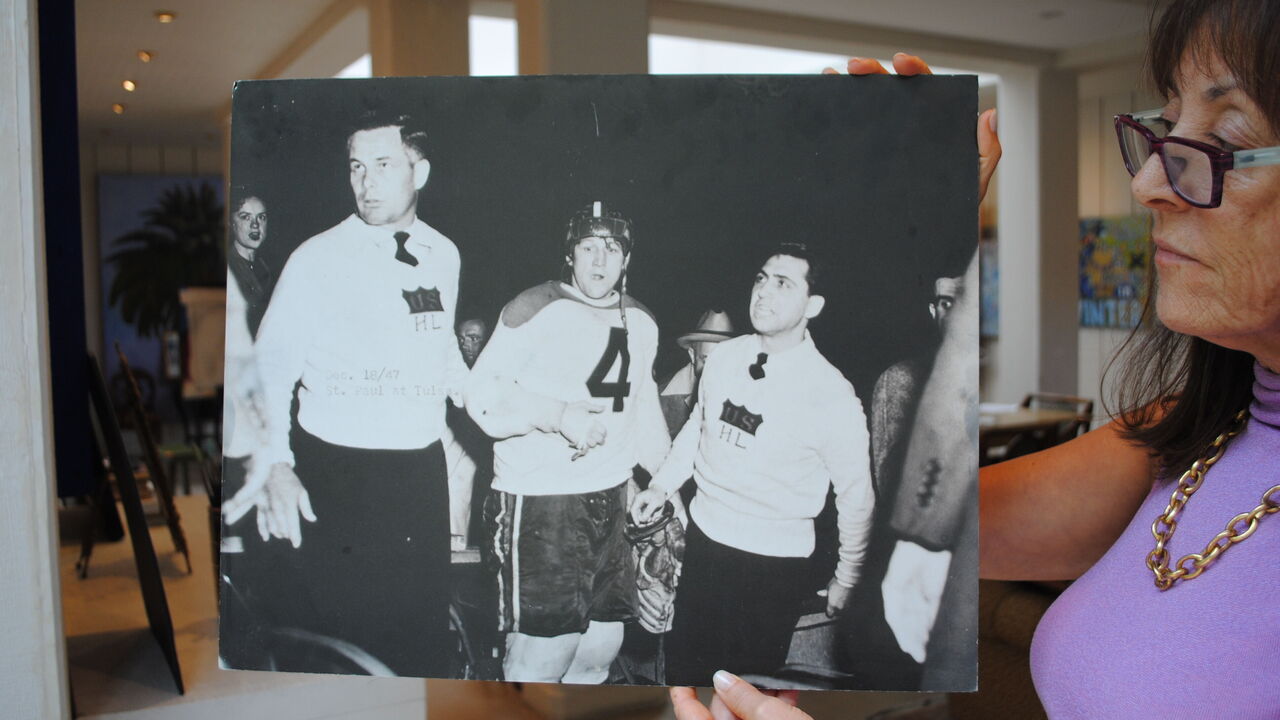

Harry Ornest was a capable athlete; in addition to hockey, he was also a talented baseball player. In 1941, when he was 18 years old, the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League invited him to a training camp staged in Southern California. He might have had a longer stint with the team, but an old friend from Edmonton - Harry Black Sr., father of current Colorado Rockies manager Bud Black - was playing hockey for the University of Southern California and invited Ornest to attend a game. When Ornest arrived, he discovered the game was on the verge of cancellation because none of the officials had appeared. Black had Ornest paged over the intercom and pressed him into service as a referee.

His baseball career didn't work out - he slept through his alarm the day after his refereeing stint - but he became interested in pursuing a career as a professional referee.

It wasn't easy to find a job, though. He offered to work for free in the Western Canada Hockey League to gain experience, but that went nowhere. Eventually, he had a chance to referee junior games for $1 a night around Edmonton. But he disallowed a go-ahead goal in a marquee matchup, and that was enough to turn the tide against him. "Ornest is a bum," coaches said, and the league agreed. He was out of a job again.

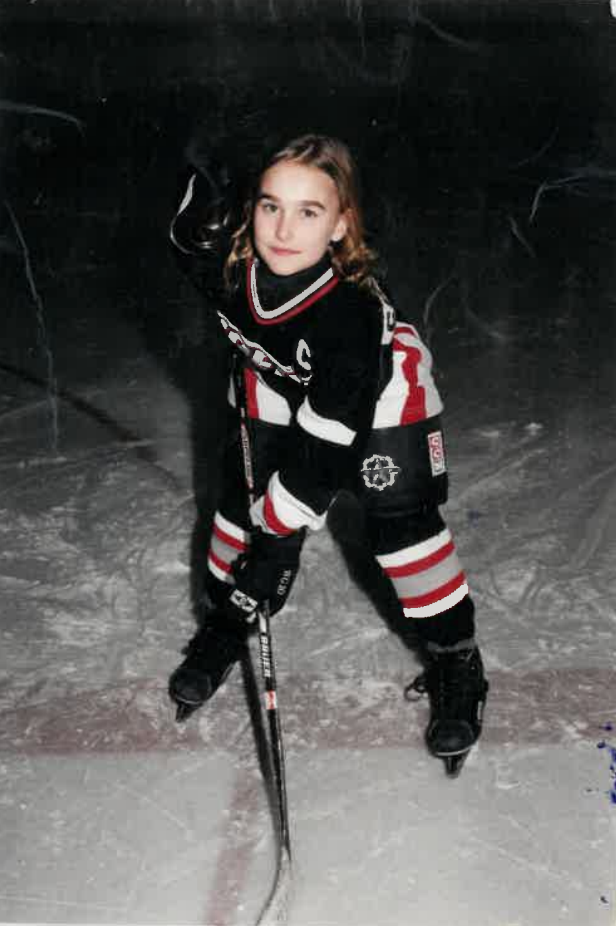

That prompted Ornest to journey south of the border where he was hired as a linesman in the United States Hockey League; he also worked some games in the American Hockey League. "He had loads of that stuff they call intestinal fortitude," a newspaper clipping he saved reads. The games were rowdy, but that suited Ornest just fine. In one particularly aggressive matchup, a fan hit Ornest on the head with a bottle, which put him in the hospital for two days. But Ornest was undaunted, and by 1948 he graduated into the NHL as a linesman. They called him "the double-barreled court of justice."

"NHL referees and linesmen have the most difficult job in major-league sports, by far," he later wrote in his notes. "Outstanding courage and stamina but faced with a game that has so many borderline judgment decisions."

In one game, he famously strong-armed his way into a fight between Gordie Howe and Maurice Richard; in the same game, he also tripped and skidded along the ice on the seat of his pants.

But the traveling life of a hockey official was not what Ornest envisioned for his future. His goal of team ownership would only become possible if he went into business and raised enough capital. While Ornest was working in the U.S., he discovered an invention that was transforming food sales: vending machines. With assurances from Campbell, who was by then league president, that he could return to officiating if his venture didn't succeed, Ornest took a risk and imported the first vending machines to Western Canada. He then added fountain soda to his offerings, storing the syrupy flavors in his basement before they were distributed to movie theaters and sporting facilities. He began to build a small fortune.

"His family came first, and he was driven to provide for his family and to succeed in the world," Laura says.

Edmonton wasn't big enough for Harry's ambitions. He soon journeyed westward to Vancouver, where there was an opportunity he thought could be life-changing: In 1962, Ornest heard the Vancouver Canucks, then a minor-league team in the Western Hockey League, were to be sold in a blind bid. Anticipating they would soon join the NHL, Ornest placed a bid. However, the team was awarded to former Vancouver mayor Fred Hume. Ornest believed Hume had been tipped off to Ornest’s higher bid and was able to increase his offer, but he couldn't prove it.

"He was angry and it was a huge disappointment," Laura says.

The Canucks did join the NHL in 1970, but Harry had already moved on - he packed up the family and went south to Los Angeles.

"I had to keep trying; you don't give up," Harry later told Laura. He likened his career to a baseball player's batting average: Successfully getting a hit one-third of the time was considered elite. He was playing the long game.

That internal wisdom propelled him for nearly two decades as he futilely tried to purchase a team. "He didn't have the money, but he had the vision," Laura says.

In a world before search engines, Harry would typically have no fewer than three newspapers delivered to his front steps each morning. He scoured their pages for hints a team might be changing owners, enlisting his four children to snip articles while he packaged annotated clippings before mailing them to decision-makers. If he wasn't doing that, he was on the phone calling business partners, journalists, and friends - trading information and trying against all odds to push his dream into existence.

Ornest's business focus expanded to producing teenage fairs in Toronto and Vancouver, but money became tight, and he eventually had to borrow from his brother to stay afloat. He reached a personal low when he applied for a job at the Los Angeles Forum.

"A true defeat," Laura says. "He had never worked for anyone. He carved his life out as an entrepreneur." Adding insult to injury, he didn't get the job. He later convinced Vancouver businessman Peter Graham to lease out the San Diego Sports Arena, which Harry operated. It was a step in the right direction, but it came with a lot of stress, and Ornest suffered a heart attack at the age of 48.

In 1977, his obsessive networking paid off when a call came in from former MLB player and manager Bobby Bragan.

"Harry, the Pacific Coast League is expanding by two teams. Do you want in?" Bragan asked in his Alabama drawl.

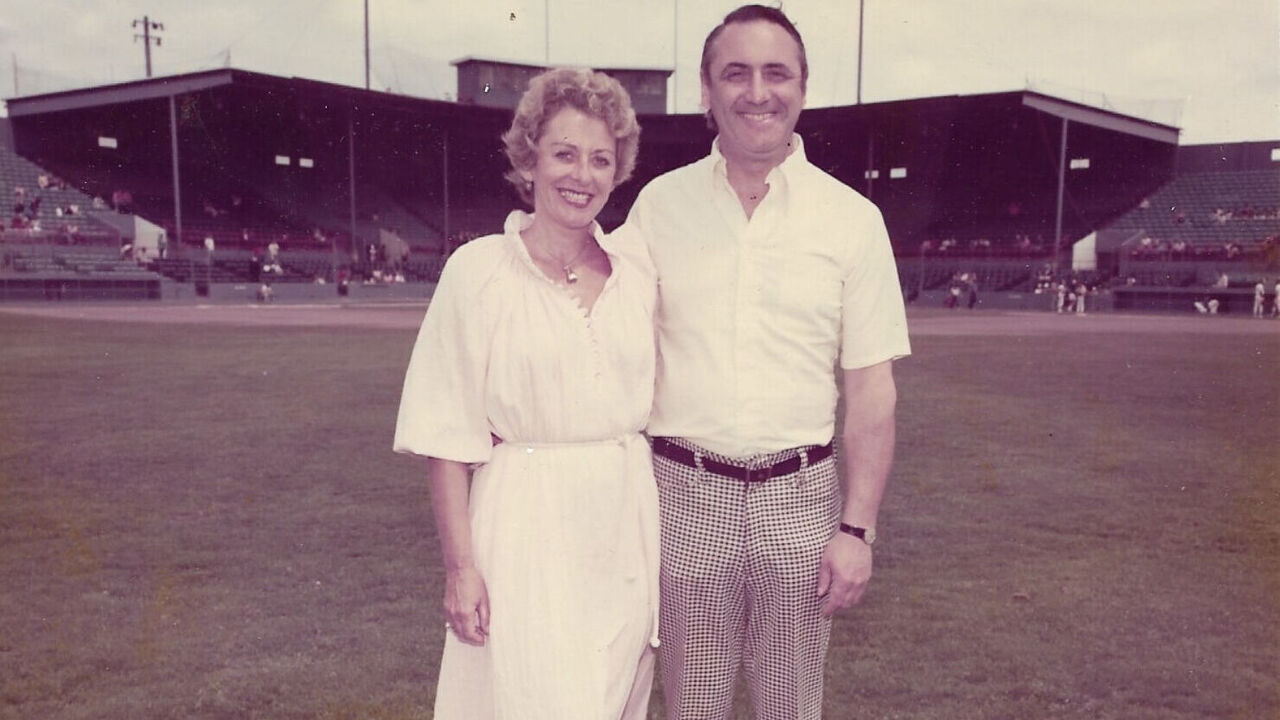

Ornest purchased the new Vancouver Triple-A franchise for $25,000 and helped his brother Leo purchase the Portland expansion team. (Leo Ornest would later win a Stanley Cup as vice president of the Calgary Flames.)

The major leagues - in any sport - were Harry's ultimate dream, but he was on the ladder now.

"The Ornest family owns the Canadians 100 percent," he wrote privately. It was a source of pride.

He shrewdly named the team the Canadians, using the alternating red and blue lettering from Molson's branding. The beer company paid him $75,000, according to his notes. At the time, it was prohibited for an alcohol company to purchase the naming rights to a team, so Ornest classified the deal as a promotion.

"Out of the fertile promoter's mind of Harry Ornest," a clipping he saved reads, "a baseball team has sprung into semi-full bloom." He set to work renovating Nat Bailey Stadium - spending $500,000 to modernize what he called "a pigeon's delight," as the facility had fallen into disrepair at the time of purchase. There were disgruntled neighbors and bylaw battles with the city, but within three years, the team was successful enough to attract the notice of Vancouver businessman Nelson Skalbania - the man who later signed a 17-year-old Wayne Gretzky to the Indianapolis Racers of the World Hockey Association. Ornest sold the team to Skalbania for $3 million in 1980.

"He really didn't have to do anything more after that and he would have been comfortable," Laura says. "But he was obsessed. He had this dream. He was always looking for more." He finally had enough money to make that happen.

The big leagues

Harry returned to California and, as was his custom, continued scouring the newspapers for a team to purchase.

"There was nobody who read the business section or the sports section of major papers in the U.S. and Canada like Harry," says Jim Devellano, the former Islanders and Red Wings general manager. "He would scribble notes in the margins like, 'This is a bunch of baloney,' or, 'Look at this, Jimmy. This would work.' I've still got the mammoth file. But at the end of the day, it wasn't a hobby for him. It was business."

Ornest didn't have to wait long before his strategy was rewarded. It was merely, as he called it, a "little squib" in the Los Angeles Times, but the January 1983 headline immediately raised Ornest's hopes.

"Hockey is Dead in St. Louis," it read.

"Suddenly, I got real interested," he later told L.A. Times sports editor Bill Dwyre. The story detailed the sordid state of professional hockey in the Gateway City: The Blues, then owned by local pet food company Ralston Purina, were to be sold to a group of investors in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

Ornest expressed his incredulity with a phrase that people familiar with his story love to repeat: "We used to call Saskatoon 'Saskabush!'" He had a firm conviction that NHL hockey could not survive in Saskatoon. At the time, its population was only about 150,000, roughly a third the size of St. Louis.

The Blues were no strangers to life-or-death circumstances; they'd flirted with disaster six years earlier. "At that time, they were the model franchise and got a lot of teams upset with them because of how much money they sunk into players," says Andy Mohler, senior sports producer at KSDK, the NBC affiliate in St. Louis. Then, the Blues were owned by insurance tycoon Sid Salomon and his son. "They treated the players to deals with a local car dealership - they all got personalized (Plymouth) Barracudas. They owned a boutique hotel that they would bring the players and families to, all expenses paid. They deferred contracts. It all came back to bite them."

The Salomons were desperate to part with the team, but no one in St. Louis made an offer. That's when Ralston Purina, out of a sense of civic duty, purchased the Blues in 1977.

The pet food company didn't have better luck running the team; the Blues' pre-tax losses averaged about $3 million a year from 1977 to 1983. Hockey as a whole was a tough business to be in at the time - 14 of the 21 NHL teams were not profitable. By 1983, Ralston Purina was just as desperate as the Salomons to rid themselves of the Blues. "They decided that civic responsibility was not their priority anymore," Mohler says.

That's when the investment group from Saskatoon, led by Bill Hunter, stepped forward with a $11.5-million cash offer to move the Blues to the so-called Paris of the Prairies.

"Of course, the city went into a sort of panic," Mohler says. The NHL blocked the sale and Purina served the league with a $60-million lawsuit while terminating over half of the team's employees.

"They basically threatened that, if this doesn't get taken care of, or you're not allowing us to sell to Bill Hunter, then we're just going to basically dry-dock the franchise, leave it at your doorstep, and be done with it.

"There were only three or four people still left in the building, one of which was longtime defenseman Bob Plager - who told me that he and a couple of assistants and the trainer would spend each day sitting in the bowels of the arena telling old stories and hoping that something was going to get resolved," Mohler says.

Making good on their word, the Blues refused to attend the 1983 NHL entry draft. "I sat at that draft at the head of the table with Detroit," Devellano says. "There was an empty table with the insignia of the St. Louis Blues."

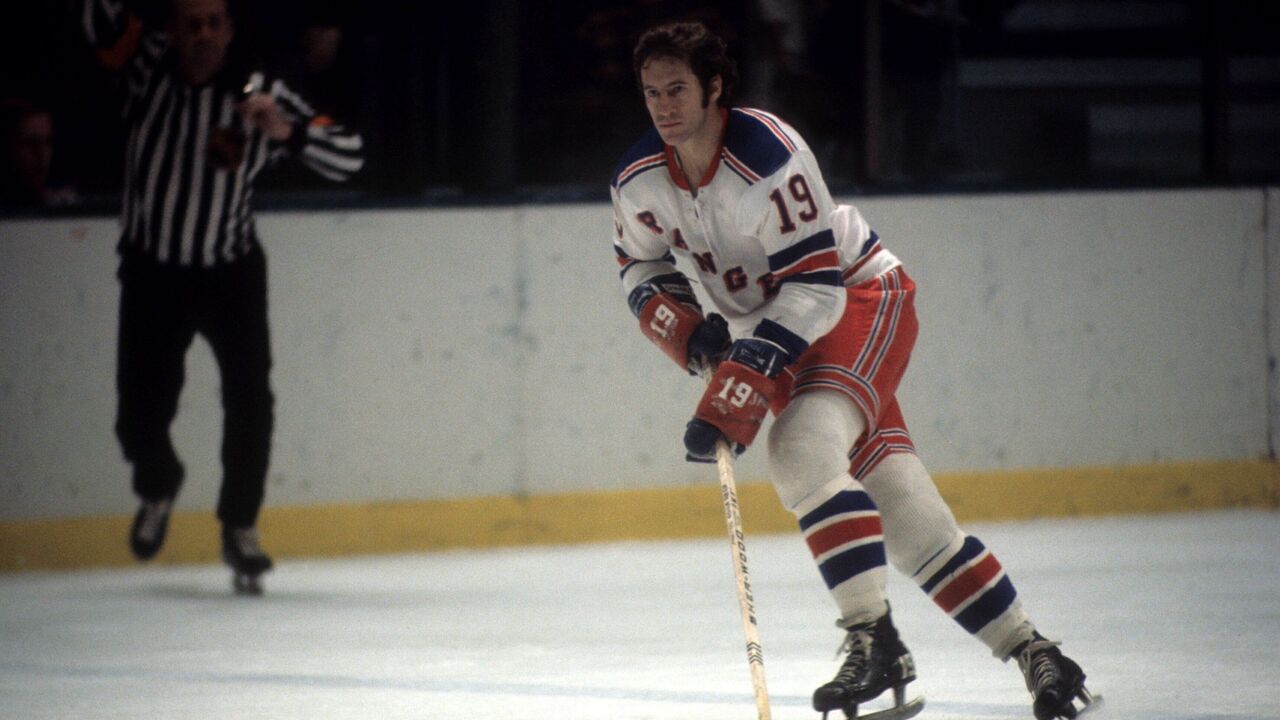

The Blues were on the brink of extinction and the NHL had already created plans for a dispersal draft of their players, which included the likes of Bernie Federko, Garry Unger, and Brian Sutter.

Enter Harry Ornest.

"He was a really tough negotiator," Devellano says. That skill was necessary for Ornest to put the finishing touches on a deal that would culminate in the achievement of his life's greatest dream. Just hours before the NHL's deadline, Ornest reached an agreement, purchasing the team and earning himself a place in the big leagues for the first time in his life at the age of 60.

The Blues sold for $3 million in cash and $9 million in unsecured notes, which didn't require interest payments until the Blues reached a certain level of profitability. Local investors put up an additional $3 million in operating capital. Ornest got 64% ownership of the team and 100% of the 17,650-seat arena he once officiated in.

"How can I describe it? It was a dream," Laura Ornest says. "This wasn't a wealthy man who was able to pursue it to make it his hobby. There was so much uncertainty, and it was stressful. But for us as a family - it was a dream come true."

The Ornest era

Harry Ornest had achieved his dream. Maintaining it was the next challenge.

"At that point, Harry was the white knight riding into town. He was a hero because there was no entity from St. Louis that was willing to take the Blues on. They had fallen on hard times," Mohler says.

Forty years later, it remains undeniable that Ornest kept the Blues from oblivion. "He was truly viewed initially as the savior of the team," former longtime Blues PR executive Susie Mathieu says. And his charisma and larger-than-life personality put hockey on the map. "He made it a lively atmosphere wherever you went, and quite honestly at that time, hockey in the United States wasn't what it has been elevated to. He could surely garner attention, press, and fan interest," she says.

"Face to face, he was a very nice man," Mohler says. "If a Girl Scout troop would call him up and ask him to come speak to them, he would. He would even miss part of a game if they wanted him to speak on a game night."

And Ornest could sell himself. "He literally would call any writer, any sportscaster, and state his opinions, and then he would send them clips," Mathieu says. "It was actually funny."

Ornest leveraged his Depression-era business sense to shift the team's financial fortunes. "If you start losing a couple of million a year on a hockey team, you get drained pretty quickly," Devellano says. "He told me, 'Jimmy, I have to be careful with St. Louis.' To his credit, he didn't get drained. He made it work. Whatever it cost him to run the Blues, he made sure that amount of revenue came in."

Ornest moved three of his adult children and his wife to St. Louis to run the team together - a family enterprise had always been central to his dream. He abruptly cut the $4.5-million payroll by $1 million and raised the average ticket price 10% to $11, dropping the Blues' break-even to 13,500 tickets sold per game. He also focused on building luxury suites, increasing TV revenue, and making the arena profitable by filling its calendar with events.

He also made some deft hockey moves, recruiting a relatively unknown Jacques Demers to coach and bringing in Montreal Canadiens legend Ron Caron as his general manager and Jack Quinn as team president.

"The romantic side of this story is how first, he saved the team. The league was gonna scrap it. They don't even (attend) the draft. Then he gets these two terrific guys - Caron, a savvy GM, and Jacques Demers as a coach, and they stay competitive," hockey historian Stan Fischler says. Indeed, by 1985-86, the Blues had turned around their on-ice fortunes. Their postseason was a memorable affair - they came within one goal of reaching the Stanley Cup Final. A stunning third-period comeback from a 5-2 deficit in Game 6 of the conference final against Calgary was dubbed the "Monday Night Miracle." But Calgary won Game 7 at home to advance to play Montreal for the Cup.

And St. Louis' honeymoon period didn't last. Ornest's personality had a dark side, and St. Louis was about to get a blast of it. "There were a lot of positives to Harry," Mathieu says. "There were also a lot of negatives on the other end of it. Chaotic is probably a good word."

As smart and charming as Ornest could be, he was also hotheaded, stubborn, and, at times, severe.

"I didn't see much of that dark side because he and I were buddies," Fischler says. "That is, until it came to the crisis over the book." Many years after the St. Louis saga, Ornest hired Fischler to write his autobiography. The project was killed after a dispute about the opening chapter, which featured a well-documented scuffle between Ornest and actor John Forsythe that occurred during a Hollywood Park Racetrack board meeting.

"He didn't become abusive, but something close to it," Fischler says. "It would have been a hell of a book."

That tempestuous nature - verging on insulting at times - was also part of Ornest's approach to the league, his staff, the city, and even the construction contractors upgrading the arena.

"I would be in these league meetings, and he'd be giving people shit," Devellano says. "Including the president of the league. He didn't make friends. He'd derail league meetings talking about the kind of money the NHL was wasting. He was a pariah in that regard. He was not popular. He couldn't afford to play with the big boys, and he knew that, so he would confront other owners and go, 'Why are you paying all of this money to this coach? Why do you pay the players all that money?' Then he'd be mad at the commissioner of the league: 'Why do you have such a big staff? I operate the St. Louis Blues with five people! Why do you have 25 people running the league?' None of the other owners talked that way."

Among the 20 other owners at the time, Ornest might have only had one true ally. "Harry's biggest pal was John McMullen, the owner of the Devils," Fischler says. "They were the two black sheep owners in the league. They weren't afraid to speak out. They didn't take any shit."

There were other missteps, too. Ornest's dream had been for the family to run the team together, but fans weren't always thrilled about their contributions. In particular, Ornest's wife, Ruth, redesigned their jerseys, a move that rankled the fan base. Harry was also maligned for trading fan favorite Joe Mullen to Calgary at the 1986 trade deadline. He insisted it was a hockey decision, but he was branded a cheapskate for not wanting to shell out the contract increase Mullen sought.

Then there is the oft-repeated story of the nonexistent team charter airplane. The true details of the event are lost to time. As the anecdote goes, after losing the conference final to Calgary, the team's charter back to St. Louis was canceled. "I don't know whether the charter was canceled because Harry was too cheap or if it was an issue with the airlines. It remains one of those mysteries that's never answered correctly," Mathieu says.

What is true is that Mathieu purchased commercial flights for the team's return trip to St. Louis. "I stayed up all night and was working to get everyone back commercially," she says. "I maxed out my credit card, and I went to Bernie Federko and Brian Sutter, who were the leaders of the team, and they let me use theirs." Everyone was eventually reimbursed for the flights.

Rumors about Ornest swirled. At some point, he had bragged about having the best coach in the league at the cheapest price. That might have been true - but it exposed a weakness ripe for exploitation. Making matters worse for Ornest, Demers didn't have a written contract extension in place, merely a handshake agreement.

That's when Devellano swooped in. "I stole Jacques Demers from St. Louis," he says. "I actually got caught tampering." His punishment from the NHL amounted to a slap on the wrist.

Ornest's reputation began to alienate key figures in St. Louis - most importantly Mayor Vincent Schoemehl. After a dispute over the city's amusement tax, which Ornest alleged was unfairly levied against the Blues and not the Cardinals, the city claimed eminent domain over the arena in 1986, professing that it needed the land for a municipal infrastructure project. The arena had been the main source of revenue for Ornest, offsetting the cost of the team. After a back-and-forth battle, Ornest conceded, agreeing to sell the team to an investment group headed by local businessman Mike Shanahan for $19 million and the arena to the city of St. Louis for $15 million. The city ultimately backed away from its plans to demolish the arena, and the Blues remained there until the team's current arena opened in 1994.

"It was sad," Laura Ornest says. "He loved owning that team. Loved it."

While Harry Ornest was romantic about sports, he was also a pragmatist. "He didn't have the financial wherewithal to compete at that level," Devellano says. "Harry was far from stupid. He wasn't going to risk the family's savings putting it all into a hockey team and going broke."

"I liked to tell people in St. Louis, after I bought the team, that I was a child of the Depression," Ornest once said to Dwyre. "I also liked to tell them that I had never really known poverty until I bought the Blues."

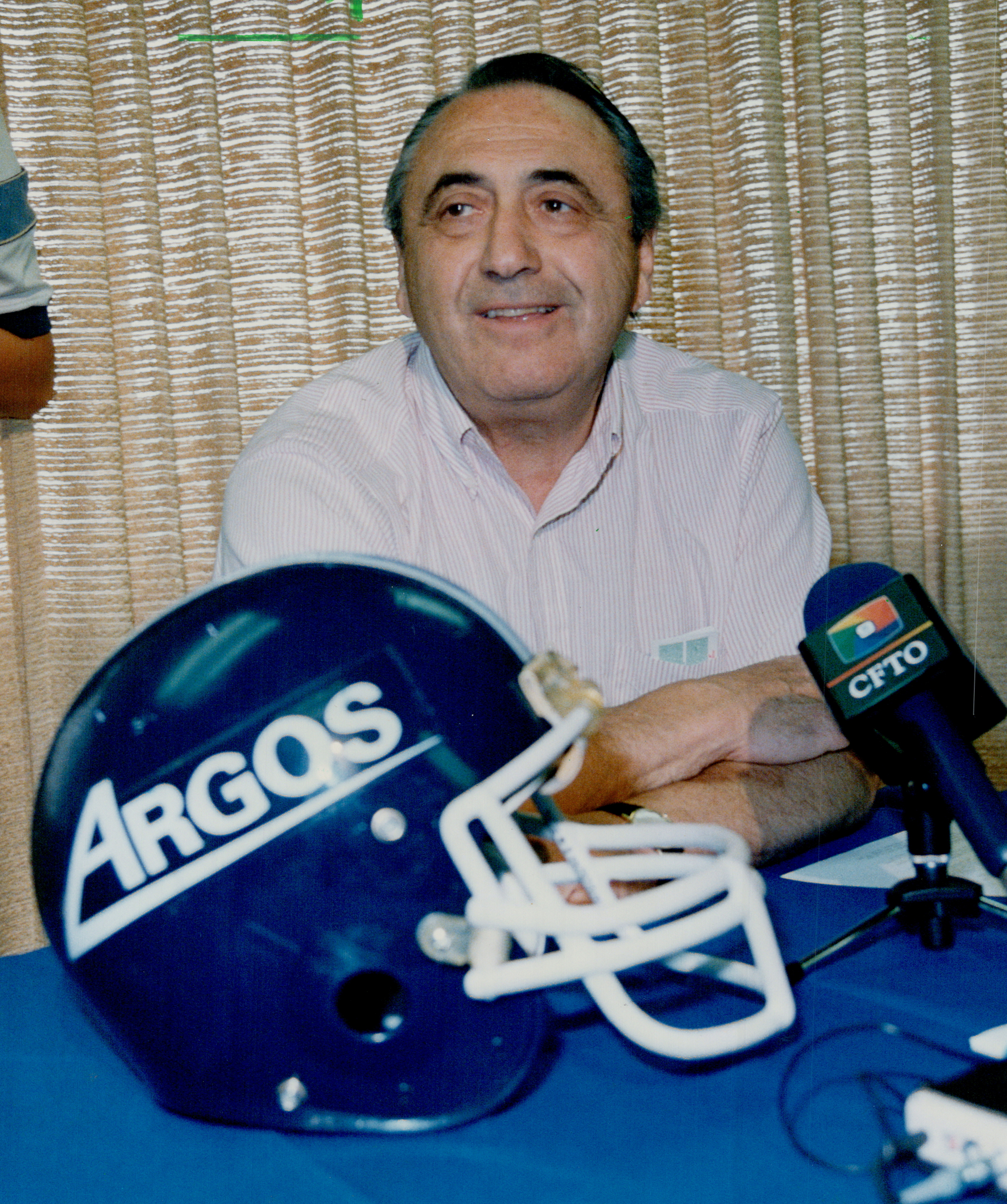

After selling the team, Ornest moved his family back to Los Angeles, but soon he was scouring the papers again for another shot at his dream. In 1988, he purchased the Toronto Argonauts, selling them in 1991 to Bruce McNall, John Candy, and Gretzky. He later purchased shares in Hollywood Park Racetrack with the aim of building a stadium on its property. Ornest died in 1998 at the age of 75, but that's the site where SoFi Stadium now stands.

"I considered him one of these fascinating curmudgeons in sports," Fischler says.

Ornest might have been an outsider who did things on a shoestring budget and let his passion get the best of him, but he did accomplish his lifelong goal. "He was an ordinary guy from Edmonton, Alberta, who wanted to live the American sports dream," Devellano says. "And God bless him, he made it."

Jolene Latimer is a features writer at theScore.

Copyright © 2024 Score Media Ventures Inc. All rights reserved. Certain content reproduced under license.