Roughly a year ago, Stephen Walkom was still processing the carnage. Over the course of the 2019 NHL playoffs, the league's director of officiating was seemingly forced to deal with a new headache involving his best referees and linesmen every time he turned around.

"Mistakes happen. Our job as officials is to recover. Last postseason wasn't easy," Walkom said in August 2019 at the league's annual officiating scouting combine. "A lot of unfortunate incidents affected results. And, our team collectively, we know we need to be better. That's life, and we'll learn from it."

This postseason won't be easy for Walkom and his crew, either, but for completely different reasons. The NHL is trying to crown a Stanley Cup champion through a 24-team tournament while the world continues to wrestle with a pandemic. Like all leagues trying to restart now, the NHL is walking a tightrope, and the health and safety of its on-ice participants is a significant issue.

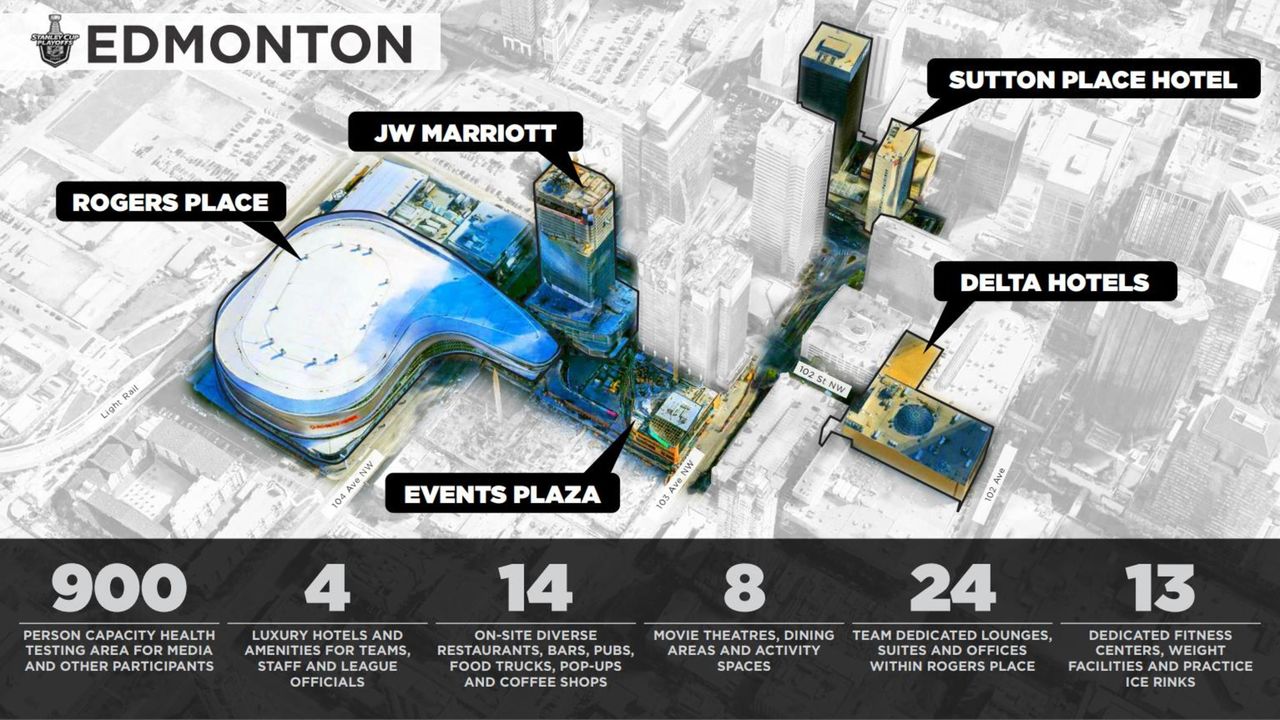

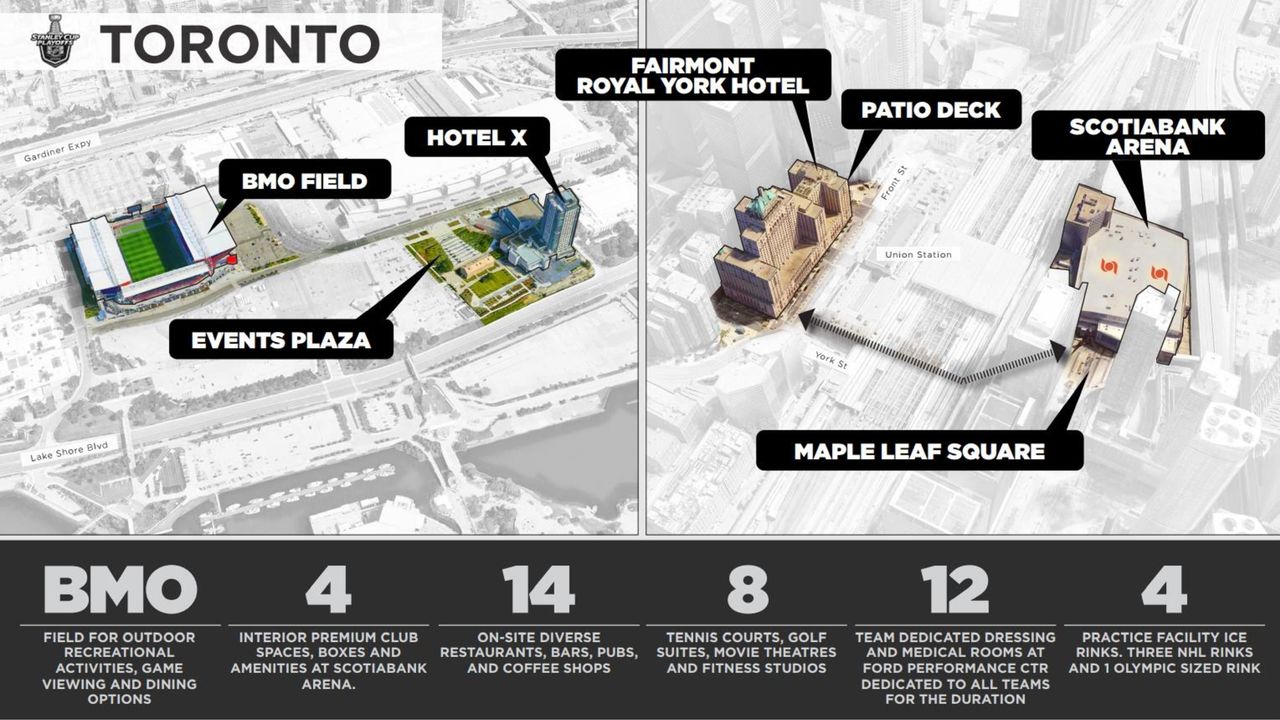

Not a single official lost their job during the league's hiatus, according to Walkom, despite the absence of games to officiate. So for the past four-plus months, management has tried to keep spirits high, minds sharp, and bodies in shape. Now, a total of 40 officials - two groups of 10 referees and 10 linesmen - are stationed in Edmonton and Toronto. Nobody tested positive for the coronavirus before commuting to their hub city and, in the few days they've been acclimating to bubble life, nobody has received a positive test.

"Our team was kept at the ready," Walkom said Friday in a lengthy phone interview, adding: "Now we know our guys are safe to go and skate."

The bubbled officials hit the ice for the first time in groups Friday and will commence two-day mini-training camps Sunday. They'll call their first games in nearly five months over a slate of exhibition games Tuesday through Thursday.

How will officials navigate the various obstacles inherent in the NHL's restart efforts? Walkom let us in on the group's mindset, role, and stiffest tests.

Is there some rust to shake off for officials since they're coming off a long layoff? It's essentially like coming out of the summer in a normal year.

Stephen Walkom: It is. To mitigate that, that's why we did the dryland training. (It helped us) simulate skating, to simulate agility and mobility. That's what we really worked on because we know that that's going to be our biggest challenge. These teams are going to come out of the gate hard. We made sure that we came into the hub early so that we'd have lots of opportunities to get on the ice and get up to speed so that our skill set would match the pace of the game. That's what we planned on doing.

From a practical perspective, how might an official's job be changed during the pandemic? Are there going to be fewer discussions with coaches and trips to the penalty box?

SW: Once you get on the ice, you're really just trying to stay out of the way. (laughs) It's probably good - at any time - to stay out of the way. But, no, I think everyone in the bubble knows that all the participants that are on the ice have been thoroughly tested. I do believe that subconsciously you're going to understand that social distancing is probably in your best interest, even if everyone has been tested. I don't even know if (officials will) have enough time to think about it out there, but I'm sure it's going to be in the back of people's minds when you're on the ice.

There's been plenty of talk about players having to adapt to buildings with no fans. How about officials? No booing, different sight lines, you can hear the players and coaches easier. What do you think it'll be like?

SW: Unless they pipe in boos, we should be good in that regard, right? (laughs) The fortunate thing is, when you're on the ice, you don't really hear much besides the people you're in tune with. It's amazing in a hockey game. You will hear a linesman's voice, but you won't hear the fans, and the linesman will be over at the (far) blue line. You will know the difference between a coach that's trying to get your attention on the bench and the player who might just be venting a little bit. It's amazing what you hear in that environment and you're almost conditioned to only hear what you need to hear.

So, I would think that you're not really going to notice as an official. If you're looking into the crowd or listening for the crowd, your focus is probably in the wrong place. And that's no different than being a player. As a player, you score a goal and you hear the fans screaming. But as you're flying up the ice and just about to beat a defenseman and then shoot a puck, you're probably not hearing anything. You're so focused in on playing. For the officials, I think it's the same thing. You're so focused in on officiating that you're really oblivious - except on stoppages - to people in the rink. So I don't know if it's going to change that much for officials. But, having said that, when you're an official and you step on the ice at the same time that a team steps on the ice, you hear the fans. You know for sure they're not cheering for you. There are times when you notice, but it's not during playing time. Do you understand what I mean?

Yeah. You're just so dialed-in. Being attentive is a big part of the job.

SW: You have to be dialed-in; A) for your safety, and B) to do a good job. You need to be absolutely focused on the game.

On a conference call with media earlier today, you talked a little bit about a new whistle for your officials. Can you expand on what's happening there? And, as a follow-up, is there anything else that's new about NHL officials in terms of equipment, uniform, or anything like that?

SW: I think that's the only thing that you'll notice, but it's not that big of a change for us. It's just a pealess whistle from Fox 40. Most people don't know, but we've been using it at the outdoor games for some time. The thing is, it has the same trill as a normal whistle, but it requires less force to blow. Less exhale. It doesn't have anything coming out of the top of the whistle, which may be better or it may not be better (for officials to use during the pandemic). I'm not a medical doctor, I've never tested it, but we thought this might be the best environment to test it in.

Was there any debate at all about officials wearing face coverings during games?

SW: No, not really. We're following the guidelines of whatever we're instructed to do, so I'm not sure what discussions went on in relation to that, but I think with all the (COVID-19) testing that they're doing, they feel pretty good about us going out there and being able to skate and do our jobs without the masks.

Are officials who get injured or fall ill going to be deemed "unfit to officiate" in the same way players are deemed "unfit to play," or is the league going to come out and say explicitly what the issue is?

SW: I think we're going to be following the guidelines no different than the players. Whoever our medical authorities are here, they'll let us know. I know that we've had two days of testing - really, we've probably had 10 days of testing (total) - and our test results have all been negative, which is good. But if someone does get injured, we are going to ensure, even for the play-in games, to have a standby referee and a standby linesman ready to go. As you know, we could have two or three games a day (in each hub city) and we don't really have a lot of time in between games. If we can reduce the time for an official to get ready, without delaying a game, we're going to do it. We hope that our guys all stay healthy, but if for some reason they don't, we'll deal with it as it comes.

Is there going to be any connection between officiating, game operations, and the broadcast? Are officials going to be mic'd-up, for instance? Be part of the entertainment at all?

SW: I'm hoping the majority of the entertainment comes from the players, but as you know, our guys have always cooperated with events (staff) in terms of being mic'd-up. We'll do the same going forward. Whatever they need us for, we'll help them out. Which is good. From what I'm told, I believe we're going to have a (microphone mounted at center ice pointed towards the top of the officials crease) for announcing penalties, so it won't be something we'll have to take off and transfer every single game. I think they're trying to minimize touchpoints in terms of the mics. You'd (normally) take off a mic and the next guy would wear it and the next guy would wear it (and so on).

As well, we're going to have separate dressing rooms. A crew will work a game, and then they'll leave, and that room will be completely cleaned. Another crew that's working the next game will be in a different room that's already been sanitized and cleaned, much like the players' dressing rooms. We're all part of making sure the dressing room is clean after each and every use to mitigate the risk of transferring anything. That's a really good thing.

What kind of treatment are officials going to receive inside the bubble? Do they have their own hotel floors? Private rooms? Will families be allowed in eventually? Can they access the same amenities as players?

SW: They've been pretty good with the hotels. Everybody has their own room. We're following the same procedures for the cleaning of your room. For our officials, if you leave your room, you have your mask on. You have a set time to be tested (for COVID-19) every day. We go down as a team, get tested, and we leave. We have common rooms to minimize our exposure to other people and other players. Everything we do, we're going to be doing it apart yet together to keep our guys as safe as possible. I think when it comes to families and such, our focus is to work the hockey games. We do understand the players and playing for a Stanley Cup and wanting to celebrate with their family. I think that's what the (players' association) is talking about. We know we're not the players in that regard.

John Matisz is theScore's national hockey writer.

Copyright © 2020 Score Media Ventures Inc. All rights reserved. Certain content reproduced under license.