During the peak of the Cold War in the 1970s, a new front opened: a cultural battle between the top hockey players in North America and the best from the Soviet Union. The winner would not just determine hockey dominance but would symbolize the triumph of an ideology.

The Soviet system had moved to the forefront of the international game, dominating the world championships and Olympics in the 1960s by skirting the rules of amateurism with jobs that allowed them to train as hockey players full-time. Professionals were not allowed to compete in these international events, so the best players from the NHL had never faced off against the dominant Soviet teams.

That changed in 1972 when the Summit Series pitted an NHL all-star squad featuring 13 future Hall of Famers against the Soviet national team. They repeated the event in 1974 against WHA players. Canada won in 1972, the Soviets triumphed in 1974.

For 1975-76, an event was planned to have two Soviet league teams play eight games in North America during December and January: Super Series '76.

"This was a groundbreaking event in not only NHL history but in hockey history. It was the first time that the Soviet teams played NHL teams, as opposed to playing NHL All-Star teams," says Ed Gruver, the author of the new book "The Game That Saved the NHL," which chronicles what happened as a result of the 1976 event both on and off the ice.

Early series results heavily favored the Soviets; CSKA Moscow, the famous Red Army team, bested the New York Rangers 7-3 at Madison Square Garden while the Soviet Wings defeated the Pittsburgh Penguins 7-4. In perhaps the most famous game of the series, the Red Army had a New Year's Eve date with a Montreal Canadiens team on the cusp of winning the next four Stanley Cups. Montreal outshot the Soviets 38-13, but the magnificent play of goalie Vladislav Tretiak earned them a 3-3 draw.

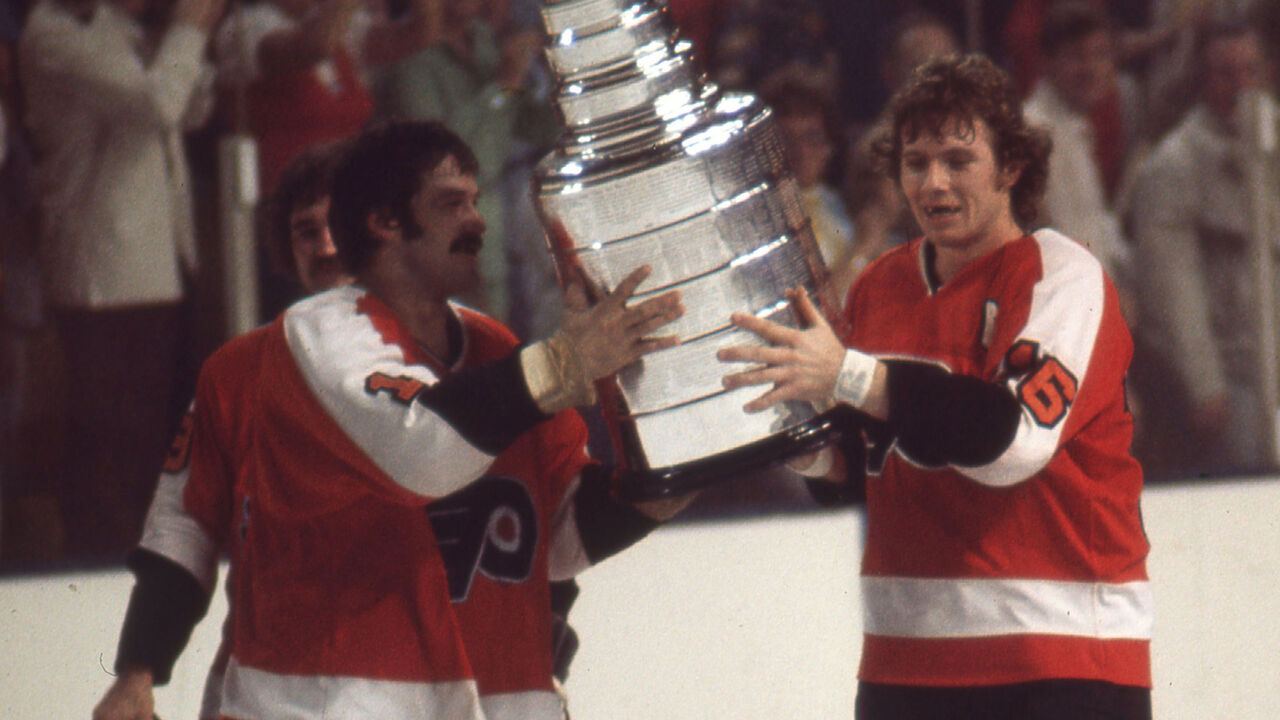

By the time the last of the eight games came around on Jan. 11, the Soviet Wings had won three of their four games and the Red Army was 2-0-1. The last NHL team standing: the two-time defending Cup champion Philadelphia Flyers.

Almost 50 years have passed since that matchup, but its results are still felt throughout the NHL today. The Broad Street Bullies, as the Flyers were then known, managed to exact a measure of revenge with a 4-1 victory.

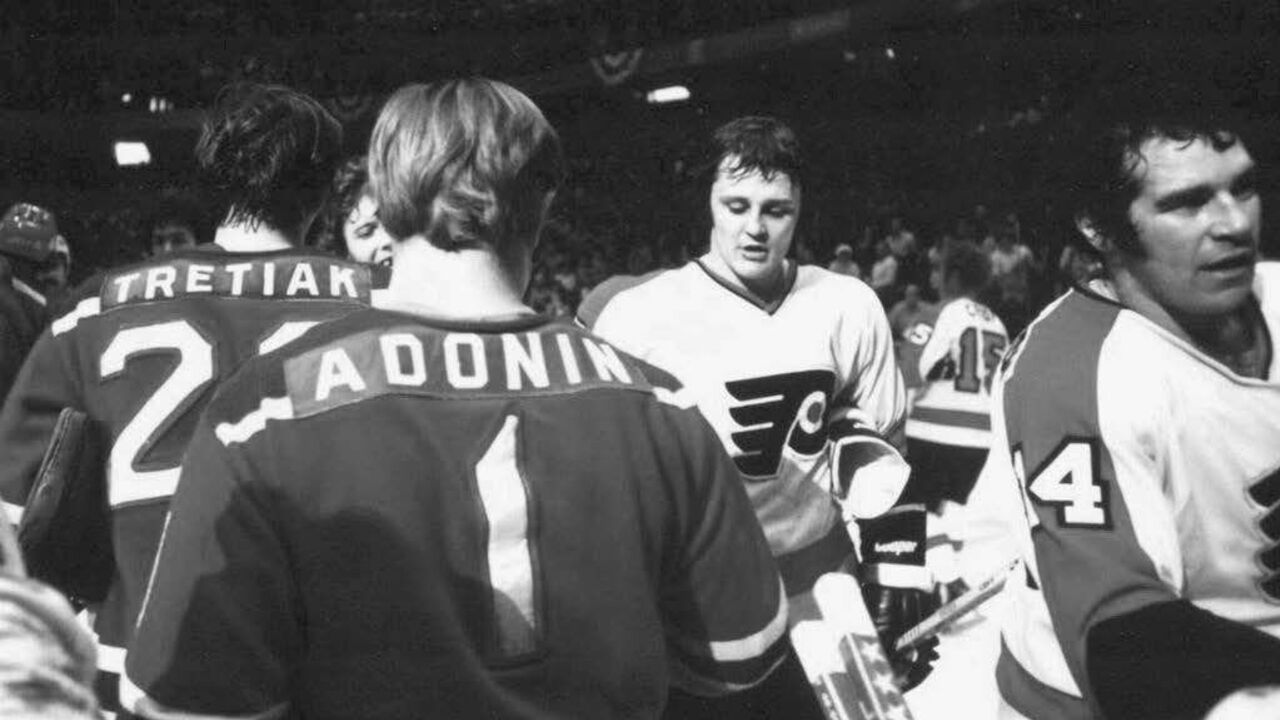

The Flyers, known for their physical, domineering approach, stunned the Soviets with their aggression, and they left the ice in protest 10 minutes into the first period. When they did return to play, the Flyers didn't back off. The crowd roared when Flyers defenceman Ed Van Impe leveled a ferocious hit against Russian star Valeri Kharlamov, whose ankle had previously been shattered by Flyers captain Bobby Clarke in the 1972 series. Still, when the final whistle blew, relations between the teams improved, with players from both sides sharing drinks in the locker room after the Flyers' win.

While that win might have saved face for the NHL, its legacy can be seen not just in what was proven that day, but in what was learned. The collision of two disparate styles of play led to significant on-ice changes for both the NHL and the Soviets. Meanwhile, the cultural significance of the series opened the door for more international competition between professionals and the eventual influx of Russian and Eastern European talent in the NHL.

theScore spoke with Gruver, whose book focuses on that final game of the series in Philadelphia as well as the impact the series had on two hockey cultures.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

theScore: Why is this an important story right now?

Gruver: Today, the story is especially important when we see relations between East and West, between the U.S. and Russia. The detente that came about after the fall of the Berlin Wall seems to be faltering again with Russia's invasion of Ukraine and all the negativity that has brought about.

Can you describe the prevailing public sentiment around mixing sport and politics in 1976?

It was very much an us-versus-them outlook, and that prevailed on both sides - whether you were North America, or whether you were Russia. Since the end of the Second World War, the Soviet Union saw sports as a way to emphasize their political system. Their teams were seen as kind of Cold Warriors. The thought was, if they can defeat North American athletes in head-to-head competition, that proves to them that the Soviet system is superior to the North American system or, you know, democracy.

The flip side was that from the standpoint of North America it was seen as: If we can defeat their athletes in head-to-head competition, we're proving that our system of government is superior to what's being practiced in the Soviet Union. It was very much an East-versus-West, us-against-them, democracy-versus-dictatorship matchup.

That's why the players who were in this Super Series, and particularly the Flyers, no team in NHL history ever felt the pressure, or will ever feel the pressure, again, of what they went through. It was left to the Flyers to uphold the honor of the NHL, which is kind of ironic because they were the Broad Street Bullies, they were almost universally hated outside of Philadelphia. But, it all came down to this.

(NHL commissioner) Clarence Campbell went into their locker room before the game and said, "Boys, you've got to win this game." The players talked about that intensity - they were representing not only their team and the NHL, but North America, our form of government, everything was on the line for 60 minutes of hockey.

If the players lose to the Soviets, then what does that mean for the NHL? What does that mean for the Stanley Cup? Now suddenly, it's all devalued? The Stanley Cup is no longer representative of the best team in hockey? Because the best team in hockey would have been in the Soviet Union. It was for hockey supremacy in the world, both sides understood that.

Was the pressure the Flyers felt for this game comparable to the atmosphere of a Stanley Cup final?

In 1972, when the Soviets played the NHL All-Stars, it was an eight-game series, and the NHL All-Stars pulled out a victory in Game 8 to win the series. Two years later, the Soviets soundly defeated the WHA All-Stars in the Summit Series. That set the stage for the Super Series in 1976 where you had the top two Soviet hockey clubs coming to the U.S. and North America to play some of the best NHL teams.

But this matchup against the Soviets and the Flyers was just a one-game situation. It wasn't a best-of-seven. It wasn't like if you had a bad game, you can rebound and come back the next night like in a Stanley Cup Finals scenario. The Red Army team were the champions of the Soviet league. The Flyers were the two-time defending Stanley Cup champions of the NHL. It was the best against best in a one-game showdown. The players (interviewed for the book) told me that the Stanley Cup pressure was nothing compared to this.

You talked to a lot of people who were present at this game, what stood out to you the most about what they remember almost 50 years later?

Talking to the players involved and the media and everyone else involved who was there firsthand, what stood out was the intensity of the series and, in particular, that final game. The schedule makers really did everyone a huge favor by scheduling that game for the final game. I'm sure it was done for a reason because they wanted to match the champions up in the climactic game. It worked out well.

The Red Army team rolled into Philadelphia to play the Stanley Cup champs and the Russians were undefeated. The Red Army team was unbeaten. There's no coming back from a loss in a one-game scenario like this.

By the 1970s, the NHLers and the Soviets had developed two distinctly different styles of play on the ice. What made their approaches both so unique?

The Soviet style was born out of a game called bandy. That was a sport that had been played in the Soviet Union. At the end of World War II, when the Russian government turned its attention away from war and to sports and entertainment, and the arts and things like that, they used the Canadian game as a building block to a point. But they more heavily relied on bandy because it was something they knew and had played. It was kind of like field hockey on ice. So the Soviets played a game that was less linear than what the NHL played.

The NHL played end-to-end hockey. They played a dump-and-chase system. The Soviets played what would be considered more of an east-to-west game with more passing. They never did dump and chase, it was short passes basically aimed at trying to lure the opposing players out of position, which would give them the best shot possible.

The NHL favored high-volume shots. They would just shoot anywhere inside the blue line and sometimes even just inside center ice. The Soviets would hold the puck for several stretches and then try to score with what they thought would be a premier opportunity. To the Soviets, a missed shot was like a turnover. The NHL didn't see it that way, they were willing to pepper the opposing goalie with as many shots as possible.

It was such a contrast between Soviet hockey and North American hockey that it was very visual when you watched the game. It's very evident that these two teams were playing a brand of hockey that was completely foreign, in many ways, to one another.

How did both sides influence each other's style of play in the years that followed?

It brought together two schools of thought on how hockey should be played. In the bringing together of these two contrasting styles, the clash between them made them both better in the long run.

Interestingly, both claimed victory in the Super Series. The two Soviet teams won the Super Series by a 5-2-1 score. But, the NHL's viewpoint was that the Soviets had beaten some of their lesser teams, but not the three top teams.

While both sides claimed victory, they also saw that they had to make changes. Following the proceedings, the Soviets began getting more physical in some of their games. They never resorted to the fighting that the NHL did, and particularly the Broad Street Bullies, but they did become more physical with their body checks and they did rely less on looking for the perfect scoring opportunity and began taking more shots.

The NHL adjusted as well. They looked to improve their conditioning, which at the time was sorely behind the Soviet conditioning because the Russians trained year-round and the NHL didn't. NHL players also looked to improve their passing, getting away from the dump-and-chase and looking for better scoring opportunities.

In your book, you highlighted that the influx of Soviet players after the collapse of the U.S.S.R. marked "the greatest migration of talent from one league to another league since the Negro Leaguers joined Major League Baseball." Was this Super Series a foreshadowing of that?

I think so, yes. You start to see more of an influx of European players into the NHL from the mid-'70s on. When the Berlin Wall came down, then you started to see a heavy influx of Russian players coming into the NHL. Both sides realized that they could benefit from the other. In the end, the real winner was the sport of hockey because it truly became a global game.

Hockey isn't regional anymore like it was in the '70s when you had North American style and European style. Now, it's more of a worldwide game. It matters less now who won the Super Series back then because the ultimate winner was the sport of hockey. The migration of talent from one league to another really benefited the sport as a whole.

Jolene Latimer is a feature writer at theScore.

Copyright © 2023 Score Media Ventures Inc. All rights reserved. Certain content reproduced under license.