Seventy years ago in Norway, Czechoslovakia's Olympic hockey captain carried an olive branch past center ice. He was about to face Canada and wanted to hand the opponent his national delegation's flag.

His sportsmanship surprised the Canadian players. They didn't have a gift for him.

"Already sadly deficient in (medals) in the 1952 Winter Olympics," The Canadian Press reported at the time, "Canada now has been caught with its courtesies down."

In 1952, Canada and the United States combined to alienate foreign teams, fans, and sportswriters, spurring some to suggest that the Olympics should drop hockey. Onlookers in Oslo objected to their physical play. The Soviet press accused both teams of fixing the tournament finale. Processing the criticism, the head of Canada's hockey association said the country should sit out future Games.

No boycott materialized, and the 1952 tournament entered Canada's lore. Only one other Canadian, speed skater Gordon Audley, medalled at the '52 Games, but the men's hockey team went undefeated. It was Canada's last Olympic championship in the sport for half a century, the wait ending once NHL stars started to play in the event.

Some Olympic tournaments are remembered for an indelible sight: 1980's Miracle on Ice, Wayne Gretzky's benching in a '98 shootout, Sidney Crosby's golden goal in 2010. One theme defined what went down in '52.

"Europeans regard the North American type of game as 'too rough,'" Robert Ridder, the manager of the American team, wrote in his post-Games report to the U.S. Olympic Committee.

That hockey was played in 1952 was a small miracle. Two rival American teams boated to 1948's Winter Games in Switzerland, inciting an eligibility dispute. The IOC sidelined the squad it preferred but, seemingly out of spite, disqualified the participating U.S. team from medal contention. Canada won gold but called the referees incompetent, bashed the quality of the Swiss ice, and contemplated skipping the next Olympics.

Instead, the Edmonton Mercurys were sent abroad in '52 to defend the title. The Mercurys were a senior amateur team bankrolled by Jim Christiansen, a local car salesman who employed several players at his Ford dealership. One veteran forward, originally from Saskatchewan, was nicknamed "Mr. Hockey." This wasn't Gordie Howe, but George Abel, an expert puck handler whose brother Sid won the Stanley Cup with Howe on the Detroit Red Wings.

The Mercurys outscored opponents 88-5 and cruised to gold when they represented Canada at the 1950 world championships. That earned them the trip to the Olympics, and they toured Europe to play dozens of exhibition tuneups ahead of the Games. On a Swedish highway, the team bus slid into a ditch and hit a tree, according to journalist Tom Hawthorn. Injuries were limited to cuts and sore backs, and the Mercurys won that night's game 7-2.

The Olympic contests were played outdoors at Jordal Amfi, a 9,000-seat rink built on time because Norwegian players volunteered to lay the piping. The Mercurys thumped Germany 15-1 in their tournament opener while wearing black armbands to mourn King George VI, whose state funeral was held in London the same day. Canada's next opponent, punchless Finland, lost 13-3 despite deploying up to four defensemen at once.

The U.S. sent a plucky, all-star collective of recent college players to Oslo. (Winger Ken Yackel, representing the U.S., was the only American in the NHL when he debuted with the Boston Bruins in 1958.) The Americans started slowly, opening the tournament with a narrow victory over a Norway team that finished winless. Up 3-2 late, the U.S. goalie was caught out of his net, but Norway's shooter fired wide from close range.

"It was at this point that coach (Connie) Pleban almost blacked out!" Ridder wrote after the tournament.

The U.S. rebounded to beat Finland 8-2 during a snowstorm - the puck came close to disappearing at points - and then blew out Switzerland by the same score. However, trouble brewed in the Swiss game. American defenseman Joseph Czarnota jumped on an unsuspecting opponent during a third-period scrum. Referees escorted Czarnota to the penalty box while the Oslo fans, some yelling "Chicago gangsters," threw orange peels on the ice.

"The 'sins' attributed to this minor American ice hockey player," The New York Times reported later, "so thoroughly disturbed (one Oslo) newspaper that it proposed the introduction into the Norwegian language of a word 'czarnota' as a synonym for cheat and ruffian generally."

Canada annoyed the locals, too. On the day of the Czarnota fracas, the Mercurys beat Czechoslovakia 4-1 in the tournament's rowdiest and most physical game. The Canadians snubbed the opposing captain in the gift exchange, then slashed, hooked, held, and hammered his teammates all over the rink.

The Mercurys took 17 penalties, and the crowd booed their barrage of body checks, "not understanding that this is all part of hockey," The Canadian Press noted. Fed up, a Swiss newspaper wrote that "overseas teams" were polluting European hockey and urged the IOC to consider dropping the sport.

"If there is no hockey in the next Olympics, they may as well cancel the Games," Doug Grimston, the president of Canadian amateur hockey, said in response, per CP.

"Hockey is the big drawing card, and no one is kidding anybody about that."

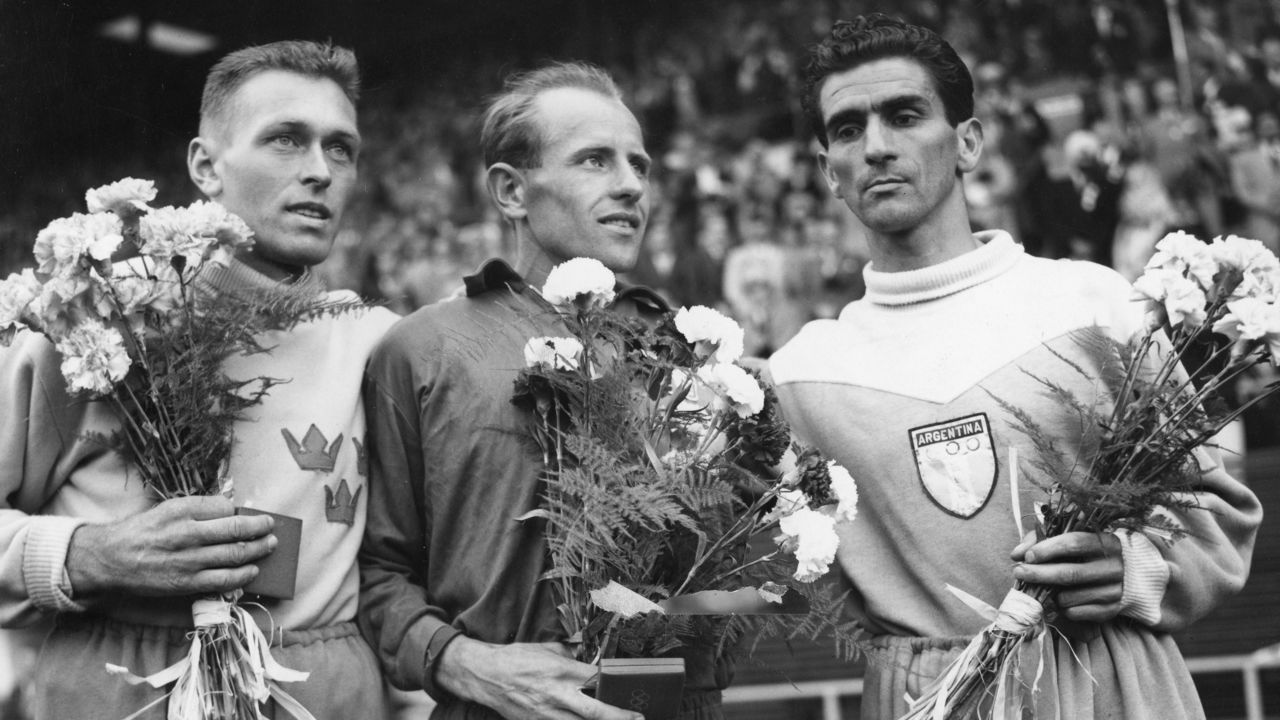

Canada's Olympic finale proved him right. Unbeaten through seven games with a plus-57 goal differential, the Mercurys had already secured gold entering their last clash with the U.S. The Americans owned a 6-1 record - Sweden beat them - and needed a point from the game to finish on the podium. A loss would relegate them to fourth.

An Olympic classic transpired. Canada outshot the U.S. 58-13 but nursed a 3-2 lead in the waning minutes when American defenseman James Sedin converted a give-and-go play. Pleban and a few players huddled at the U.S. bench and decided to sit back to protect the tie.

"The Canadians had come to the same conclusion themselves and literally froze the puck for the remaining three minutes," Ridder wrote afterward.

"At the final whistle, both teams poured over the boards in sheer delight - the Canadians because they had won the championship, the Americans because they had tied the invincible Canadians and won what seemed an impossible silver medal."

United Press International reported that "stony silence" greeted the Americans at the closing ceremony, though the Mercurys sparked laughs by showing up in cowboy hats. All the while, anger over the standings festered behind the Iron Curtain. The Soviet Union didn't play in Oslo, but the Moscow newspaper Trud claimed Canada and the U.S. conspired to tie so communist Czechoslovakia wouldn't medal.

"We expected something of that kind from Russians," Ridder told reporters, per The Associated Press. "I suppose the Reds cannot lose without throwing dirt on victors."

Eager to chime in, Grimston called the accusation "about the stupidest thing I've ever heard" and later grumbled the Mercurys weren't reimbursed for their expenses while touring Europe. He told reporters that Canada ought to pull out of future Olympic tournaments.

Grimston was blustering - Canada went to the next Games and placed third - but it took time to resolve the transatlantic schism. At the Summer Olympics in Finland later in 1952, the great Czech distance runner Emil Zatopek set records in the 5,000 meters, 10,000 meters, and marathon, which he entered on a whim. His motivation to dominate was unusual.

"It was the brutal and harsh play of the United States ice hockey team in the Winter Olympics which drove me to my most recent performances," Zatopek said, per The Associated Press. "I made a pledge to win at least two gold medals for my country."

By then, the Mercurys had secured their place in history. Edmonton held a victory parade in the city center when the team returned, with players riding in Ford convertibles down Jasper Avenue as 70,000 people cheered. Christiansen, the team owner, died of pneumonia not long after the Olympics, and a group of players, including captain Bill Dawe, took over his car dealership.

While Sid Abel's Red Wings won the Stanley Cup in 1952, George Abel headed home to Saskatchewan, where he kept playing senior hockey and helped run his family's hauling business. He died in 1996, six years before Canada's next Olympic hockey triumph.

The Toronto Maple Leafs invited Dawe to a tryout when he returned from Oslo, making it possible the Mercurys would graduate a player to the NHL. Dawe, who wasn't a bruiser at 165 pounds, accepted the offer but didn't last long with the Leafs.

"He probably would have made the team," Dawe's son told the Toronto Star many years later. "But he said, 'I'm too small, and those guys hit too hard.'"

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.

Copyright © 2022 Score Media Ventures Inc. All rights reserved. Certain content reproduced under license.