In Game 4 of the Eastern Conference Final, as the Tampa Bay Lightning built what proved to be an insurmountable series lead, Brayden Point passed the puck in the neutral zone and beelined to the foot of the New York Islanders' crease. Ondrej Palat's return feed found him there, and Semyon Varlamov splaying to cover his glove side was the only resistance Point met. He whacked the disc over the goal line, then skated away with his arms raised.

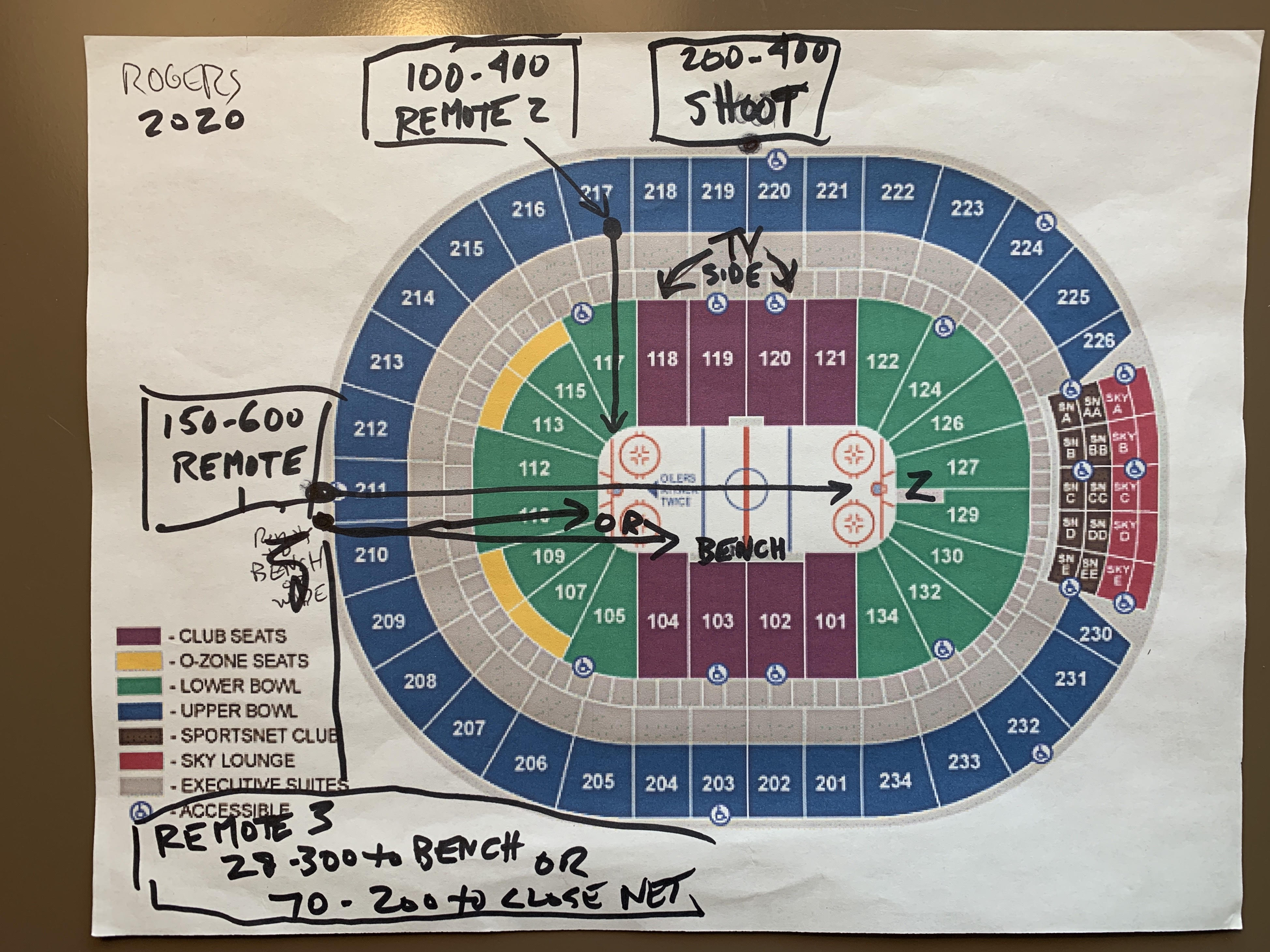

As Bruce Bennett sees it, the NHL playoffs are unfolding inside two kinds of bubbles. One is the stronghold that has housed Point and Varlamov's squads during their time in Toronto and, from the conference finals onward, Edmonton. The second is the scene Bennett observes from his perch in the uppermost deck at Rogers Place, where a camera he positioned high above the visitors' net captured Point's jubilance - and the Islanders' corresponding angst - 200 or so feet across the rink.

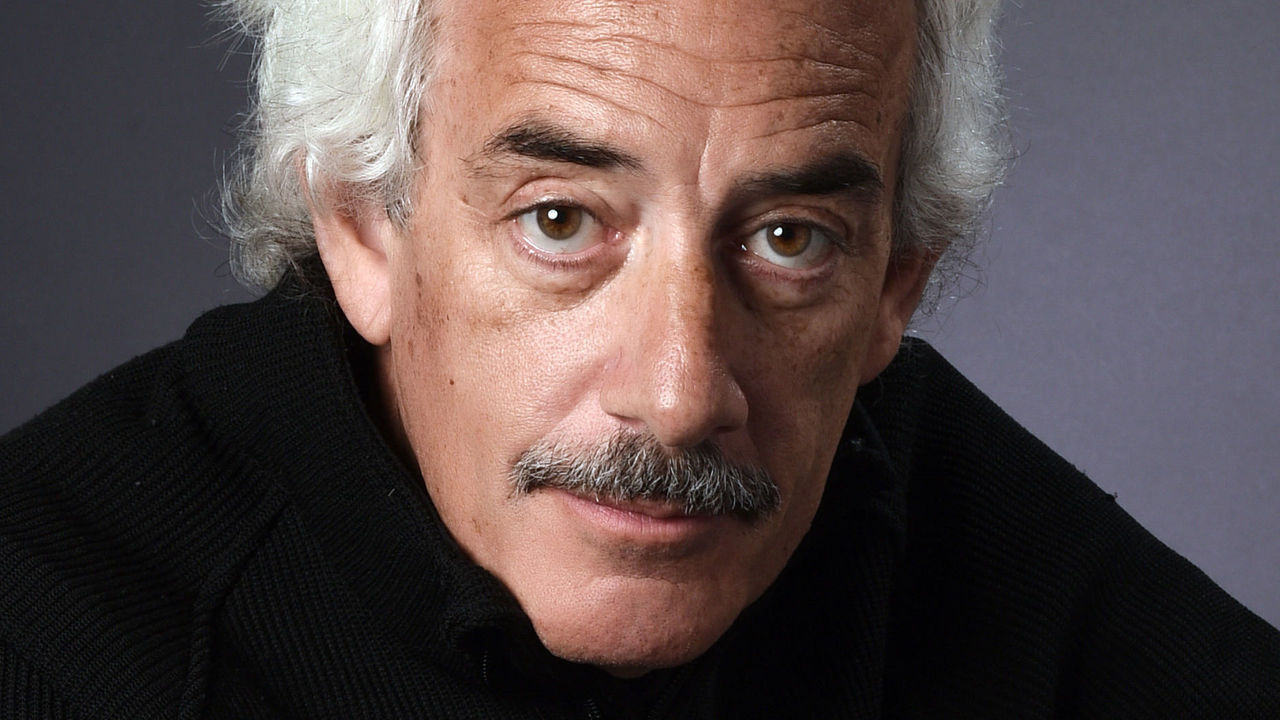

Bennett, 65, is the prolific Getty Images photographer whose work appears atop and throughout this story, like it has in most every publication that's covered hockey over his 45 seasons in the game. He's used to shooting from ice level, risking the odd cracked rib or head wound from an errant puck - more so in the old days, before protective plexiglass was omnipresent - to record history in real time from point-blank range.

But few precedents have persisted in 2020. Bennett isn't staying in the league's secure zone, and strict coronavirus protocols govern movement inside the arena. That's why Getty's Edmonton operation is based at center ice far above the fray, as if Bennett is watching and chronicling table hockey matchups from an impassable remove.

"Instead of playing bubble hockey with rods, and twisting those rods, I'm playing (with) cameras, twisting and contorting myself shooting from a photo position that's not conducive to the kind of photography that I like to produce," Bennett said in a recent phone interview.

"There's a lack of intimacy when you shoot from a higher angle. You don't have what I always stress in hockey photography: the faces. You don't have a good look at what the players are going through. Here, I look at the top of a lot of helmets. Occasionally, I can get a face. But it's a very different form of photography - a very different way of seeing the sport."

Few people have witnessed more NHL action than Bennett since the dawn of the league's expansion era. The mustachioed Long Island resident has shot, to be painstakingly precise, 5,157 games in dozens more arenas than are now in use, though primarily from the nearby home barns of the Islanders, New York Rangers, New Jersey Devils, and Philadelphia Flyers.

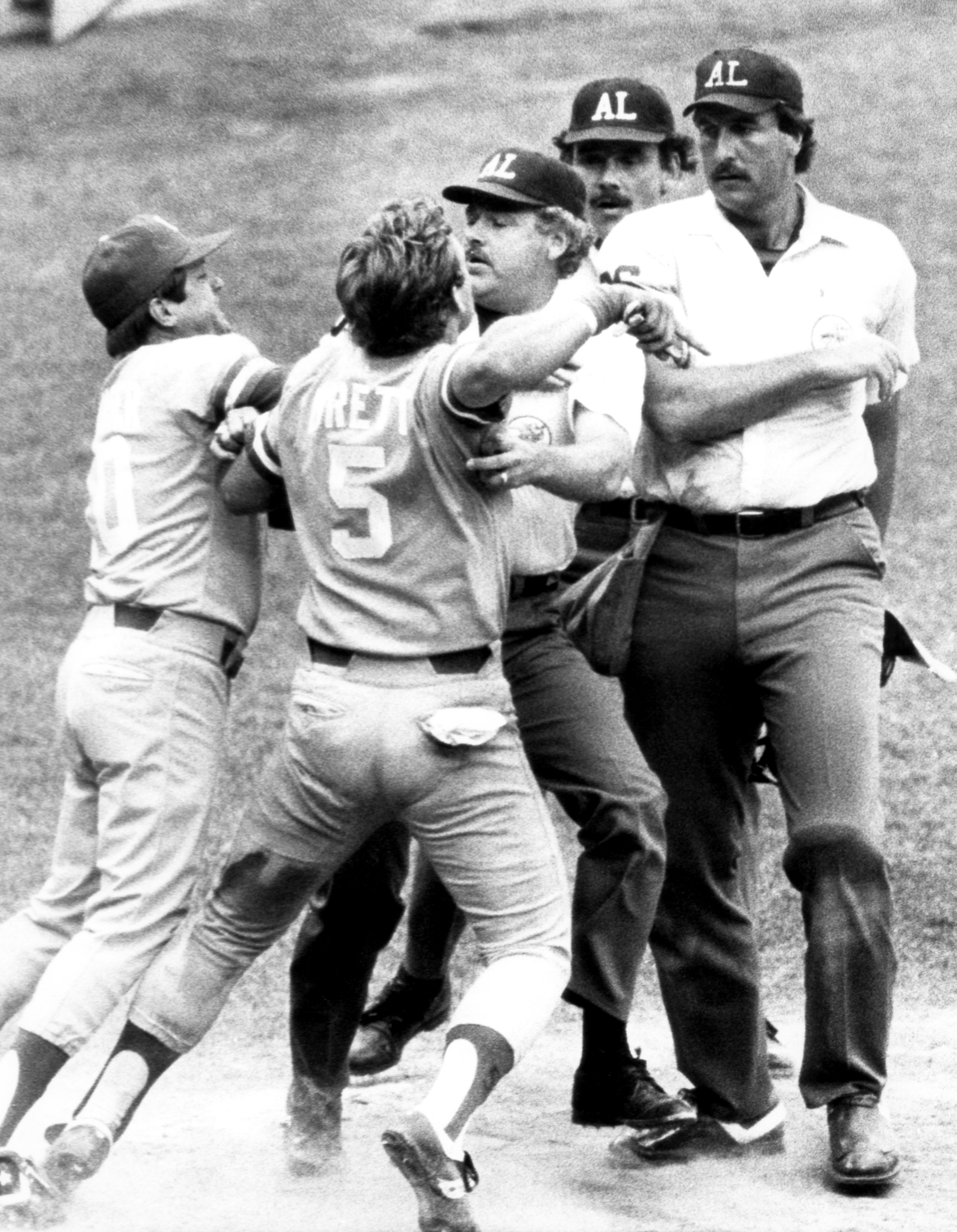

Bennett's bio isn't all hockey - he happened to be at Yankee Stadium the day Kansas City Royals third baseman George Brett was busted for pine tar in 1983 - but it does account for the lion's share of his career highlights. His marquee assignments include five Olympic tournaments (Lillehammer, Nagano, Vancouver, Sochi, and PyeongChang), eight World Hockey Association games in the 1970s (some involving Wayne Gretzky, then a prodigy on the verge of debuting in the NHL), and 39 matchups that decided the Stanley Cup champion. A milestone 40th beckons at Rogers Place within the next 10 days.

Only a handful of photographers, two of whom the league hired to stay in the bubble and shoot from ice level, are on site in Edmonton, where Bennett emerged from a two-week hotel quarantine early in the second round. Tapped by Getty to work the playoff stretch run solo, he employs four cameras to supply diversified imagery to the agency's worldwide clientele: his handheld Canon 1DX Mark III, plus remote devices stationed around the rafters that focus on points of interest, including one goal line, the team benches, and the net at the opposite end.

Bennett couldn't make use of that last angle if a crowd was present; the netting that usually rises from the back glass would obstruct the camera's sightline on plays such as the Point goal. The confines of his vantage point necessitated creativity, and the result is a lot of shots from a bird's-eye view.

Via Bennett's Instagram, here's William Karlsson (goal-line cam) celebrating a goal; the Dallas Stars (bench cam) toasting John Klingberg; the Lightning (bench cam aimed instead at the nearest net) soaking in another recent win. If those pictures each told a night's story, another snap got at the larger spirit of this bizarre postseason.

Conversations with Bennett about his craft can cover wide ground. In a call with theScore not long before the Stanley Cup matchup was set, he lamented his inability to stick a camera in either net - that right has been reserved for Dave Sandford and Andy Devlin, the NHL Images lensmen in Edmonton - and reflected on his encounters with a few compelling and legendary subjects.

Here's Bennett's take on Sandford's iconic shot of Nazem Kadri's round-robin buzzer-beater: "Stellar frame. I envy him being able to put that net cam in almost every night. There are times when people ask me about my net-cam shots and I minimize the amount of work that goes in there by saying, 'You hold that button down for 12 frames a second, hoping that something's going to happen.' But Dave's (not only) an extraordinarily talented photographer, but also has a tremendous sense of timing. It's setting up the camera correctly and giving yourself the best chance to succeed in an image like that. That will go down as a very historic frame."

Bennett on the unique appeal of photographing Scott Stevens and Mark Messier up close: "Both those guys, you would see the fire in their eyes. You would be able to tell whether those players or even others were motivated to play the game - whether they were in the zone."

Bennett on photographing Gretzky in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1979: "He was a scrawny kid once. Look what he (went on to do) … It was key for me that year to photograph Gretzky because the following year, (he and the Edmonton Oilers) were going to be entering the NHL. I wanted to make sure I had something of him in a WHA uniform."

Bennett on the chaos of Stanley Cup celebrations in the 1980s: "Here in Edmonton, I came off the ice one year, and I had a flash on the top of a camera that was broken off. My watch was missing. It was a vicious, vicious time. … I couldn't tell you which year that was, but I was right in front of (Gretzky), and he's looking with fear in his eyes and just going, 'Back up! Back up!' I'm going, 'I'm trying to back up.' There was so much pressure and force behind us. There were 30 guys at that time running around the ice, trying to get exactly the same image."

The task of shooting the on-ice merriment that caps every postseason has become less physical and more civilized, Bennett said, thanks to the NHL limiting the number of people with cameras allowed over the boards. Victorious players can skate without bumping into bodies or tripping on wires, and Bennett has leeway to block out the noise and focus on preserving the scene in its entirety. "Every single guy who holds up that Cup is important," he said, be they a first-liner, Black Ace, or besuited staffer he identifies by their name tag.

Bennett has experience snapping Cup celebrations from upstairs: He sought out that angle in two past go-rounds in a bid to get creative but came away unsatisfied. Consider it a welcome possibility, then, that he might be permitted to descend from high above when the Lightning or Stars clinch this year's title. The NHL confirmed to theScore that its medical team is helping devise a plan to let all photographers present cover the trophy handoff from the ice.

Bennett operated independently for a few decades before he joined Getty in 2004, when the agency obtained his studio's trove of 2 million hockey images - originals and many more archival acquisitions - that date as far back as the early 1900s. No game in that comprehensive historical span has looked quite like what's gone down in the bubble, where simulated crowd noise has alternately helped Bennett lock into the action and provided a laugh when the roar arrives a beat late.

It's another reminder that these playoffs have no precedent. Bennett said he's been happy to be there, familiarizing himself with Western clubs he doesn't often see and managing any attendant irritation.

"At times it's quite frustrating, shooting from the position that we're shooting from," he said. "But it's a challenge, as well. If you don't rise to the challenge, you might as well just quit the business. The goal is always to get the best photos, and a good photographer should be able to do that from anywhere they're placed in a hockey arena."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.

Copyright © 2020 Score Media Ventures Inc. All rights reserved. Certain content reproduced under license.