On Sunday, chartered planes in 22 NHL cities across North America will take off carrying professional hockey players, coaches, and staff. One of two Canadian cities will be the destination: Edmonton for those from the Western Conference, Toronto for those in the East. The Oilers and Maple Leafs, "home" teams by geography only in an ambitious 24-team playoff tournament set to begin next Saturday, will be there waiting.

Once on the ground, those groups of up to 52 people from each city - "traveling parties" is the official NHL term - will be transported by bus to assigned hotels. Proper physical distancing will be expected en route and as buses pass into fenced-in areas surrounding Sutton Place and the JW Marriott in Edmonton, and Hotel X and the Fairmont Royal York in Toronto.

Everyone from the star forward to the backup goalie and from the equipment manager to the social media manager must follow the same protocol once inside one of these four high-end hotels. The hub-city "secure zones," or bubbles, are designed to shield all participants of the NHL's return-to-play efforts from the coronavirus, the cause of the pandemic that halted the 2019-20 season on March 12.

"Paramount in everything we've done to date and everything we'll be doing moving forward is the health and well-being of all NHL personnel," commissioner Gary Bettman said Thursday in a video presentation released by the league.

Ultimately crowning a Stanley Cup champion in October amid a pandemic - easily the greatest logistical undertaking of Bettman's 25-year tenure - will rely upon the tightness of these bubbles over the coming weeks.

Can they pull it off? We'll see. A better question right now might be: What do players think of the bubble and what will soon be their new reality?

"We don't really know what to expect, to be honest with you," Avalanche captain Gabriel Landeskog said last week as details were still being ironed out. "But, at the same time, it'll be like a little tournament. We're used to going to tournaments as kids (where) you're together as a team."

"Maybe guys will get a couple of mini sticks and have some good old times," Canucks forward Tanner Pearson added, half-jokingly. "I would imagine that we'll have a common room or something, where we can all hang out and at least get out of our rooms and not lay in our beds all day."

It turns out amenities in both cities will be fairly extensive.

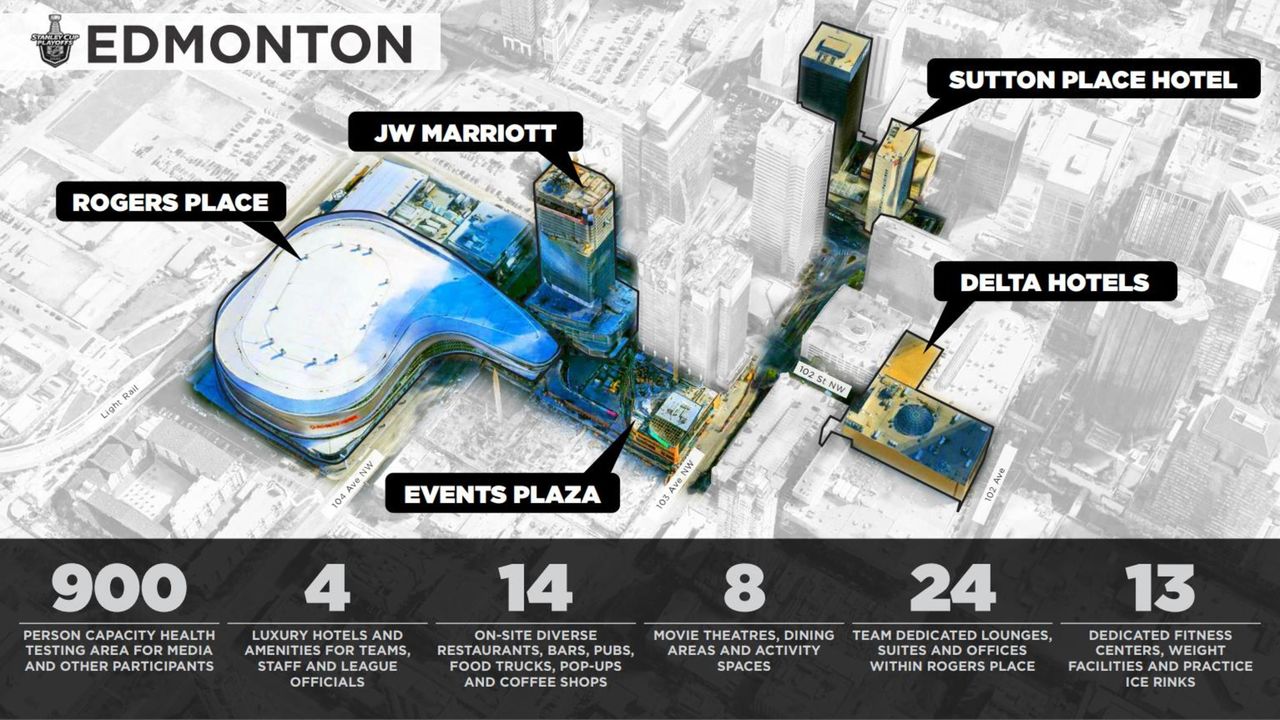

Edmonton's secure zone, which includes the two team hotels, a third hotel for overflow staff, an events plaza, and Rogers Place, offers 14 restaurants, bars, pubs, food trucks, and pop-ups. On-site food options range from tacos to Tim Hortons, while concierge service is available for orders at grocery stores, pharmacies, and other restaurants within the city.

Also in the Edmonton bubble are eight movie theaters, dining areas, and activities spaces; 24 lounges, suites, and offices within Rogers Place; and 13 fitness centers, weight facilities, and practice rinks. Among the activities the NHL is promising players are pingpong, cornhole, basketball, and soccer.

"We're hoping our lifestyle, food-wise, doesn't change," Blues forward David Perron said. "We're guys who like to take care of ourselves, who like having good, healthy food. It's nice every once in a while to have a cheat day and eat whatever you want, but I think it's important that we're being taken care of that way."

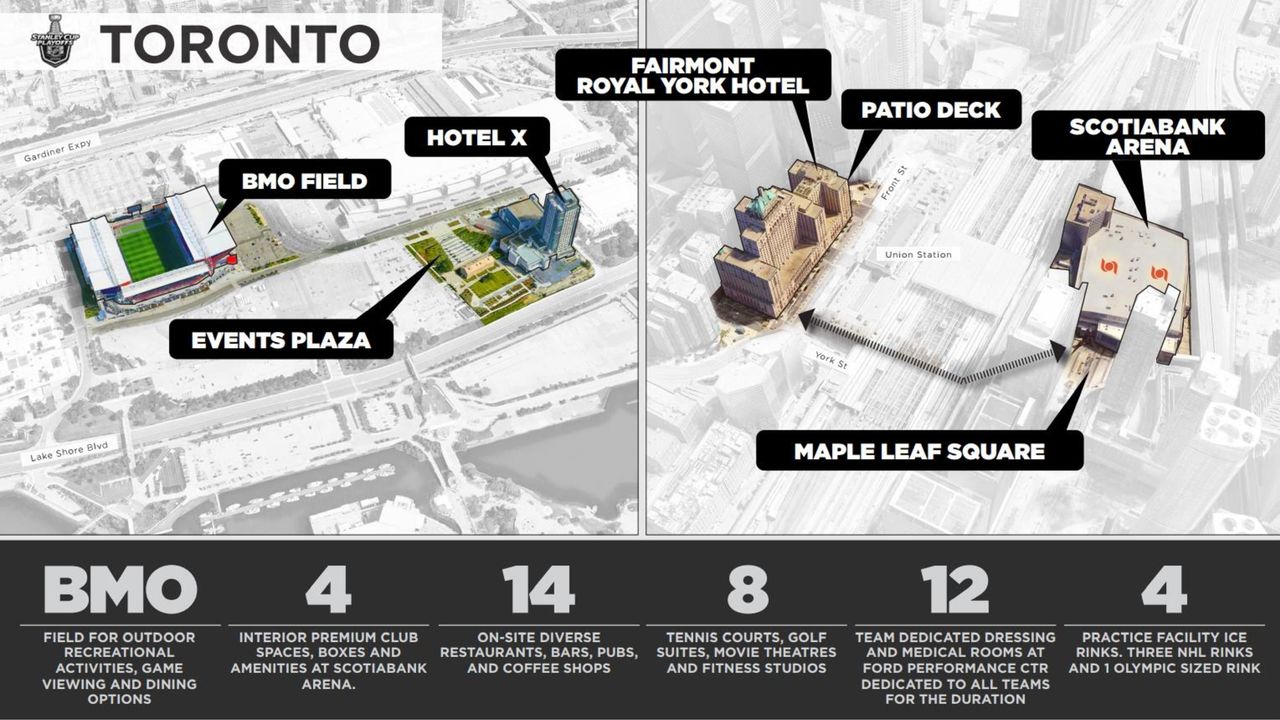

Toronto has two secure zones - one downtown near Scotiabank Arena and another a few blocks west at Exhibition Place, a mixed-use district in which Hotel X is located. Similar to Edmonton, there will be plenty of bars and restaurants, movie theaters, and team-dedicated rooms within the confines. Noteworthy perks: players will have access to BMO Field, home of Major League Soccer's Toronto FC, for leisure purposes - pickleball is being promoted as a marquee pastime - and the league's secured private access to the underground tunnel that connects Scotiabank Arena and the Fairmont Royal York.

The most interesting part of both setups might be that players are being encouraged to watch other games from suites inside the arenas. It's kind of like a minor hockey tournament, after all.

"Appreciate what you have," Stars forward Joe Pavelski said. "We get to play some hockey, and we get to get back to compete. It's going to be unique as far as a bunch of teams in the same hotel, games going left and right once they get started. And no fans."

"You have to keep a mental sharpness, in a sense where there's going to be a lot of time in the hotel rooms," Coyotes forward Derek Stepan said. "In order for us to do this thing right, guys have to be really smart. You've got to be able to keep your head on your shoulders, stay sharp, and not get into dulls and lulls and have good energy when you come to the rink. I think that's a mental toughness thing."

Meanwhile, inside the hotels, every player is assigned his own room on a floor exclusive to the team, according to the NHL's Phase 4 health and safety protocol. No guests are allowed in private rooms - not even teammates, coaches, or staff. Housekeeping staff will be limited to every third day.

Hotel pools are open, but saunas, steam rooms, and spas are not. Fist bumps, high-fives, and handshakes are big no-nos, and face coverings must be worn at all times, with obvious exceptions, such as eating and exercising. And no talking during elevator rides, which have rules regarding physical distancing.

So far, the NHL's avoided a major outbreak; only two players tested positive during Week 1 of training camp out of a pool of more than 800. Teams have handled daily COVID-19 tests throughout Phases 2 and 3, but they'll pass that duty to the league upon arrival to hub cities. Those inside will be tested daily and know results within 24 hours.

These are high stakes from a health perspective and a competitive perspective. The protocol document states that breaking rules in the bubble environment could result in "significant penalties, potentially including fines and/or loss of draft picks."

"Leaving the bubble is just not something that we can tolerate," Bettman reiterated in the presentation. "Everybody's used terrific judgment to this point, and I know that we can count on everybody moving forward."

"I'm just trying to have an adequate number of shows downloaded before I get up to Canadian Netflix," Lightning goalie Curtis McElhinney quipped. "I'm not sure what to expect. I don't know what our lives are going to look like once we're up there. I think the teams, the organization, and the NHL are trying to do their best to make sure that everyone feels comfortable and accommodated. It'll certainly present its challenges, but it'll give us an opportunity as a group to spend a lot more time together."

The Lightning's longest road trip this season lasted two-and-a-half weeks. A Stanley Cup favorite ahead of the restart, Tampa Bay's now bracing for a lengthy stay at Hotel X. Players could conceivably be living in the same room for weeks, potentially months, with the last possible day of the Stanley Cup Final tentatively scheduled for Oct. 4.

"We're going to bring a lot more stuff than when we go on a normal road trip. You plan on being there for two months," Panthers forward Jonathan Huberdeau said.

"Travel's just getting there, and once you get there you can set up," Pavelski said. "You don't have to pack up every other night. You can get your room how you want it and go from there."

Capitals goalie Braden Holtby plans to bring one of his guitars; Maple Leafs defenseman Jake Muzzin won't forget his golf putter; Bruins forward Charlie Coyle is making room in his luggage for supplements and healthy snacks; Jets defenseman Luca Sbisa has "loaded up" on books; Hurricanes forward Jordan Martinook will be recruiting teammates to play the board game Super Tock; Rangers forward Ryan Strome fully expects poker games to commence in the team's common area; and seemingly every other player headed to one of the hub cities is ensuring all video game devices - XBox, PlayStation, Nintendo Twitch, etc. - are accounted for.

There should be fewer formal suits spotted this postseason. The players' association negotiated a looser game-day dress code into the resumption of play agreement, and Leafs center Auston Matthews and other fashion-forward NHLers expressed their excitement. Meanwhile, the Wild, the West's 10-seed, instituted a casual dress code featuring team-issued collared shirts and matching pants.

Steve Mayer, the NHL's chief content officer, said Friday that players were told "in a very stringent tone" to remain separated from players from other teams for the first five days of the bubble experience. It's uncertain how much, if any, inter-team mingling will be permitted following those initial guidelines, but the idea of two bitter on-ice rivals grabbing a beer at the hotel bar on an off day is intriguing.

"That's going to be the real neat part, being in the same hotel as the teams you're playing against. That'll be different," Holtby said. "There's so many quality people around the league on different teams. I think guys can turn it off pretty quick once you get away from the game to see old friends and that kind of thing."

"It's going to be hard not to see the other guys," Sbisa said. "You're going to share elevators on your way up to your floor. You're going to see all the other guys, so it's definitely going to be different. But it's going to be the same for everyone. Everyone is in the same boat. Everyone has to deal with the same thing. It's an even playing field."

Depending on who you ask, the concept of a bubble's no big deal. These players are adults and professionals. The issue is leaving family behind. Families aren't permitted inside the bubbles until the conference finals, which will take place in Edmonton in September.

"I'm not worried about me," Jets captain Blake Wheeler said. "I'm going to be around my teammates, I'm going to be in a hotel, and playing hockey, really. For me, the hardest part is going to be everything going on back home. (My wife) and our kids and how all of that's going to work on the day-to-day. So that's going to be the hardest part, sort of weighing those things and being out of touch with that aspect of things. It's been four-plus months of doing it together and to just kind of up and leave is definitely tough. But it's all part of what I do for a living."

Players can leave the secure zone for only three reasons: to receive medical assessment or care; to get a second opinion on a health matter; or to return home for an urgent matter, such as a death in the family. If a player does leave - Washington's Lars Eller said he'll likely leave for the birth of his child - he must pass four consecutive COVID-19 tests over a four-day period before returning to normal bubble activities.

"I was quite against the league and the PA when it came to not being able to bring our families from the get-go," Golden Knights goalie Robin Lehner said. "I had a lot of discussions with them about that. … It's not just about the players' mental health, it's about the families' mental health, too. There's a lot of players with young kids and wives and stuff, and we're going to leave them at home, alone, quarantined in the house with the kids. It's going to be equally as tough for them as it is for us."

Players are about to enter the unknown on the ice - playing in empty arenas after a very long layoff - and off it. The integrity of the entire return-to-play plan rests on members of each traveling party looking out for themselves and one another.

"I've seen some quotes from other guys around the league saying, 'We have food, we have a bed, we have the boys,'" Strome said. "When you're on the road, I think that's all that goes on. It's just a good time to bond."

John Matisz is theScore's national hockey writer.

Copyright © 2020 Score Media Ventures Inc. All rights reserved. Certain content reproduced under license.